Prior post: http://blog.bucksvsbytes.com/2021/08/06/road-trip-21-06-21-the-mccarthy-road-former-railroad-track/

[NOTE: Some displayed images are automatically cropped. Click or tap any photo (above the caption) to see it in full screen.

Wednesday dawns (once again, a figure of speech since it never got dark) bright and blue. Bonnie brings down more hot muffins and we eat a hearty breakfast before I tackle the flat tire issue.

Everyone living in remote Alaska needs an array of tools in order to be self-reliant so I’m sure the B&B owners have something as basic as an air compressor. Of course they do, so I drive the van over to their garage building and pump up my seriously deflated tire for the short trip to the flat fix guy’s shop. It turns out to be at one of the local airstrips, the one where aircraft are fueled up.

He’s a little late, so I occupy my time watching the air-related activity. A helicopter pilot is gassing up her 1994 Aerospatiale before rising into the sky (since my first experience in 1981, I’m always a sucker for helicopters) and another pilot accelerates his plane into flight along the gravel runway. When I lived here even some major airports lacked paved runways. In the 1970s, Wien Air Alaska became the first carrier to operate scheduled Boeing 737 jet service onto gravel runways in rural areas. When both aircraft are gone, a fuel truck pulls up to replenish the aboveground tanks of aviation gasoline.

The tire guy arrives and introduces himself as Kaleb. He gets right to work and when he gets the wheel off the van and the tire off the wheel, we see that, as I thought, a nasty chunk of metal has penetrated the tire. It’s near the edge of the tread, angled in sideways so the interior end of the puncture is very near the sidewall. Normally, repair of such damage would be considered unsafe and the tire would be scrapped. The rules are a little different in McCarthy, though, since I’m at least 300 miles from a shop that might sell my size tire.

Kaleb does a “best practice” repair of the puncture and remounts the wheel. Neither of us knows how long the tire will remain serviceable but at least it’s holding air now. His fee is only $30 — extremely fair considering where we are and that he could name almost any amount and get it from me. In isolated communities, it’s good practice to treat people well because you may need their help tomorrow, although there always seems to be one outlier who abuses everyone.

Whether the repair is permanent or not, the problem is solved for now and the trip can proceed apace. I drive back to the cabin and thank our hosts profusely for their help. We pack up our gear and head back to the McCarthy Road, 3 miles away. Before tackling the 62 mile westbound drive back to Chitina and pavement, we take a short hike up the west side of the Kennicott River toward the icy toe of the glacier.

The trail is only 1.2 miles long and starts out through a mosquito infested forest. I deal with it by wearing my hat and pulling up the collar of my long sleeved shirt and swatting a lot, but Susan goes further and puts the mosquito net over her hat and head. She’s wearing a skirt, as usual, despite my endless warnings about what impractical hiking garb that is. She really dislikes wearing pants, though, so off we go.

The trail is level and about a quarter mile out emerges from the forest into scrub vegetation and onto a 4-wheeler (ATV) trail. The mosquitoes thin out and Susan removes the head net.

We’re the only people on the trail this morning, which now runs along the base of a high gravel bluff, the lateral moraine debris deposited when the glacier extended down the valley much further than it does now. These moraine bluffs, composed of lightly consolidated gravel, lend themselves to landslides and we cross a couple of major, but old, slide scars where the trees have been wiped out.

Beyond the bluff, the trail drops down off a bench to a lower level of old glacier bottom. The transition involves a steep section of trail about 50 feet long with loose gravel footing. Susan is very nervous about any steep downhill and this one merits caution. I advise her that she should slide down this section on her butt — no big deal in jeans, but quite difficult in a skirt. After trying to avoid the inevitable, she does the slide, but very awkwardly while attempting to avoid thigh skin-to-trail contact.

Once at the bottom, the trail resumes a flat but rocky course toward the edge of the ice and meltwater pools.

When a glacier recedes, the melting ice exposes bare, soilless bedrock. This area is slowly recolonized by plants. In warmer southeastern Alaska, the progression at sea level from bedrock to mature rain forest takes only about 200 years. Here, up north, at 1400 foot elevation and in a much harsher climate, the succession takes much longer. Low plants and some bushes have taken hold but there are still many exposed rocks colonized by a variety of colorful lichens.

In case you forgot your high school science, although I’m sure it’s still fresh in your mind, a lichen is not a plant. It’s a symbiotic community consisting of a fungus, an alga, and (only recently discovered) a yeast. The fungus secretes acids and can thus absorb minerals directly from rock, the alga photosynthesizes food, and the yeast, perhaps, contributes physical structure to the group. This 3-way partnership benefits everyone and as a result lichens are found almost everywhere there is light.

Glacial moraines often have interesting rocks because most of them have been transported many miles on the ice so one area can display quite a bit of variety.

Where we’re walking, there’s quite a bit of conglomerate, rock created from ancient river deltas where pebbles of various sorts have been compressed into a matrix of mud or silt. It’s sometimes called puddingstone. I’ve always found these interesting and attractive and Susan is fascinated by the geological history they represent.

The sky is almost cloudless and we have an unobstructed view of the Kennicott and Root glaciers as they cascade from the high icefield down a steep slope many thousands of feet high.

We also have a clear view of the Kennecott Mill over 3 miles away.

For me, it’s always more rewarding to experience my surroundings off the road. In part, it goes back to my German-rooted belief that if you’re not suffering, you’re missing out on the good experiences. Scenery seen from the car window is vastly inferior to the same view after a hard hike up a rough trail — in a cold rain.

After enjoying our rugged surroundings and expansive views for a half hour or so, we backtrack the same route to the trailhead and the van. By coincidence, we’ve timed our hike just right as the high overcast starts to move in and obscure the blue sky. The 2.5 mile walk yields an epochal benefit — after years of resistance, Susan declares that bluejeans are a necessary accommodation for the outdoors. Hallelujah! The walk is also an important precursor to another long day on the road. Our drive back to the resumption of pavement in Chitina is uneventful. We take it slow and stop to admire various scenes.

The tire holds, as I suspected it would, and we gain confidence that we can proceed as planned rather than shooting straight to Anchorage where car problems can be more readily dealt with.

Retracing the Edgerton Highway from Chitina, we’re treated to dramatic views of some the Wrangell Mountains. They’re no longer totally obscured by clouds as they were on our way in because the overcast is now higher than the peaks.

The highway tees and we turn south back onto the Richardson to make the 86 mile dead end drive to Valdez. The road and scenery will be familiar to me because I drove there many times while I lived in Alaska.

The road follows valleys through the center of the Chugach Mountains. This is the northernmost segment of the Pacific Coast Ranges, which ends rather dramatically at the eastern edge of the flat peninsula occupied by the city of Anchorage. The Chugach range is extensive, 250 miles from east to west and 60 miles from north to south — about the size of all of Switzerland — with peaks ranging to 13,000 feet. Bear in mind these extensive mountains are just a small piece of Alaska as a whole.

About halfway along, the flat valley runs out and the road starts to climb toward a pass.

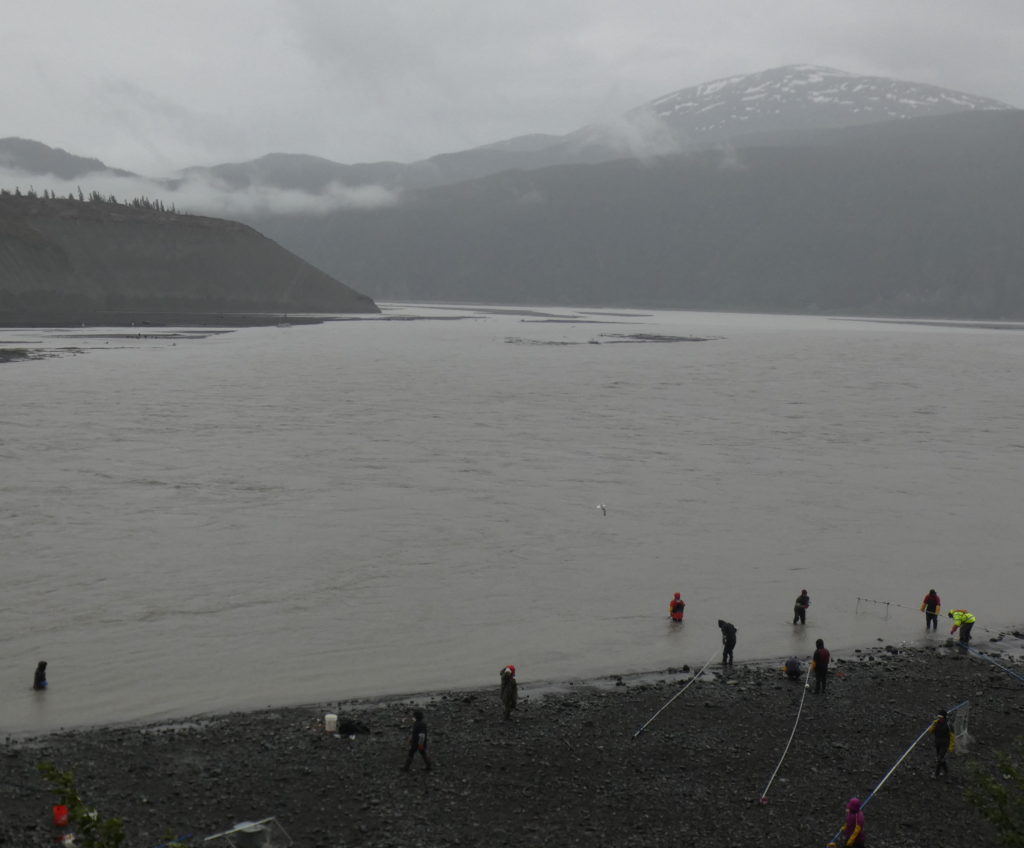

High mountains surround both sides. Even in June they’re sheathed with a lot of snow. Hanging valleys are always above us, many still containing the valley glaciers that carved them. Waterfalls descend from every one. Valdez and its surroundings get a lot of precipitation and today is no exception. We make the transition from high overcast to low clouds and quite a bit of rain. I don’t consider this bad weather because it’s a major part of the area’s dramatic beauty.

As we climb, a turnoff to the right accesses Worthington Glacier, one of Alaska’s few “drive up” glaciers. Because we want to get to Valdez before the hour gets too late, we take a very quick look and move on.

The road continues to climb to Thompson Pass, only 2600 feet high but the recipient of a prodigious amount of snow in winter, averaging 500 inches. The very important Richardson Highway from Fairbanks to Valdez first carried auto traffic in 1913, but for decades was closed in the winter because the Alaska Road Commission presumed the pass could not be kept clear of snow. In 1950, a freight company foreman took it on himself to plow the road all winter to prove it could be kept open and thus shame the Commission into taking on the job. Imagine how frustrated and angry you’d have to be to go to those lengths. He picked just the right time to set the precedent, too, because 3 years later the Commission had to cope with a Thompson Pass record of 974 inches of snow!

In summer, we don’t have to deal with any of that and just enjoy the change from lush vegetation to harsh tundra and back to lushness as we descend.

On the Valdez side, the road goes through Keystone Canyon, a short but impressively narrow cleft with almost vertical walls formed over the ages by the Lowe River. The high walls feature a dozen or more significant waterfalls on both sides draining the high, alpine slopes. We breeze by this, too, in our desire to reach Valdez and knowing we’ll be coming back this way on the way out of town.

The last 17 miles into Valdez is through the flat flood plain of the Lowe River, still surrounded by high mountains of which we see only glimpses through the low clouds. Our main concerns right now, after 9 PM, are finding an open restaurant for dinner and a place to sleep since Valdez has never been known for great food and economical overnights. Dinner is procured at an Asian restaurant, because it’s about the only place still open. Fortunately, the food is good and the price reasonable. To Susan’s surprise, their menu includes bulgogi, a Korean dish she hasn’t eaten in many years.

After our meal, 10 minutes of driving around the small town yields an inconspicuous place to park in a large gravel patch adjacent to Mineral Creek. Now that we’re 250 miles south of Fairbanks, there’s at least a pretense of darkness for a few hours, but we’ll sleep through it on our comfortable airbed in the van.