[NOTE: To enlarge any image, right click it and choose “Open image in New Tab” or similar.

Yesterday was, frankly, boring. I drive 740 miles across the Canadian prairie, cruising northwest across Saskatchewan and Alberta, got an oil change and ate a meal in Edmonton and completed the torturous required “Day 1 in Canada” mandatory Covid test. This has to be done under the video supervision of a nurse and when I go to the website (apparently designed by a high school slacker during video game pauses) I’m told I’m 350th in line. Mercifully, the number decreases pretty quickly and after only 2 hours or so I’m able to make the nasal swab, seal up the envelope, and drop it off at a nearby ship point. All of that uses up the day.

On Saturday, though, things get a little more interesting as I move into rolling hills and true north country. From my improvised sleeping spot northwest of Edmonton (it was a gratifyingly cool 46 F when I awoke), I continue up Alberta Highway 43 which, along with a stretch of British Columbia Highway 2 brings you to Dawson Creek BC and the official start of the Alaska Highway..

Unlike the “old days”, Hwy 43 is completely modernized, transformed from a gravel road into a divided 4-lane highway with breakdown lanes, a wide right of way, and plenty of services. In other words, boring.

I’m surprised, though, to still see microwave relay towers along the route.

In the pre-satellite, pre-fiber optic 1980s when I lived in Alaska, the only means of long distance telephone transmission was via microwaves. Long chains of line of sight towers were constructed over thousands of miles of remote territory. A dish antenna on one side picks up the signal from the prior tower, the signal is processed in the hut at the base, and retransmitted on to the next tower in line. Most towers were off the electric grid so they had their own diesel generator and needed regular fuel deliveries, generally by airplane or helicopter. There was no alternative across these vast stretches of often roadless northern territory. Now, with more advanced technology, I’m surprised to see such antique transmission still in use, but there the towers are.

By early afternoon, I reach Valleyview, Alberta, notable mainly because it’s where the two primary northern routes diverge. If I bear right, I would eventually arrive in Wrigley, deep in the Northwest Territory, along the banks of the mighty, north flowing MacKenzie River.

Instead, I stay left continuing on Highway 43 toward the Yukon Territory. The divided highway continues for another 90 miles, turning into a still very modern 2-lane route for the last 30 miles to the British Columbia border, which persists the rest of the way to Dawson Creek.

Dawson Creek was the start of the Alaska Highway, the initial version of which was built by the US Army, 1700 miles slashed through forbidding terrain in just 8 months. Although contemplated for many years, the attack on Pearl Harbor and subsequent declaration of war with Japan made it a strategic priority. When first completed it was a very rough route, suitable mostly for heavy military vehicles. Although the highway became very important in opening Alaska to the “Lower 48” states, ironically, it was not of great immediate strategic importance as most wartime goods were shipped by sea from Seattle when it became apparent that the Japanese didn’t project much naval power to those sea lanes.

Downtown Dawson Creek is still pretty recognizable since I last drove to Alaska in 1977, but the town has sprawled into the surrounding area. The “Milepost 0” monument is unchanged.

Even as it opened, the highway was being improved, a process that continues to this day. Over its 80 years, over 300 miles have been cut by straightening out its contour-following, “just get it done” original alignment. In many places along the road, you can see earlier versions of it either as abandoned stubs or local byways.

Just 21 miles out of Dawson Creek is a good example of both “version 2” construction and abandoned alignments. The original route involved a difficult fording of Kiskatinaw Creek. Within a year or two, a 100 foot high, curved, wooden trestle bridge was built to cross the steep valley. This was in use for about 35 years despite the fact that vehicles exceeding the bridge’s 25 ton limit still had to use the old ford through the creek. In 1978, a new all-traffic road was built that bypassed the bridge, which was still used for local traffic. In recent years the bridge was closed entirely and now serves only as an historical attraction.

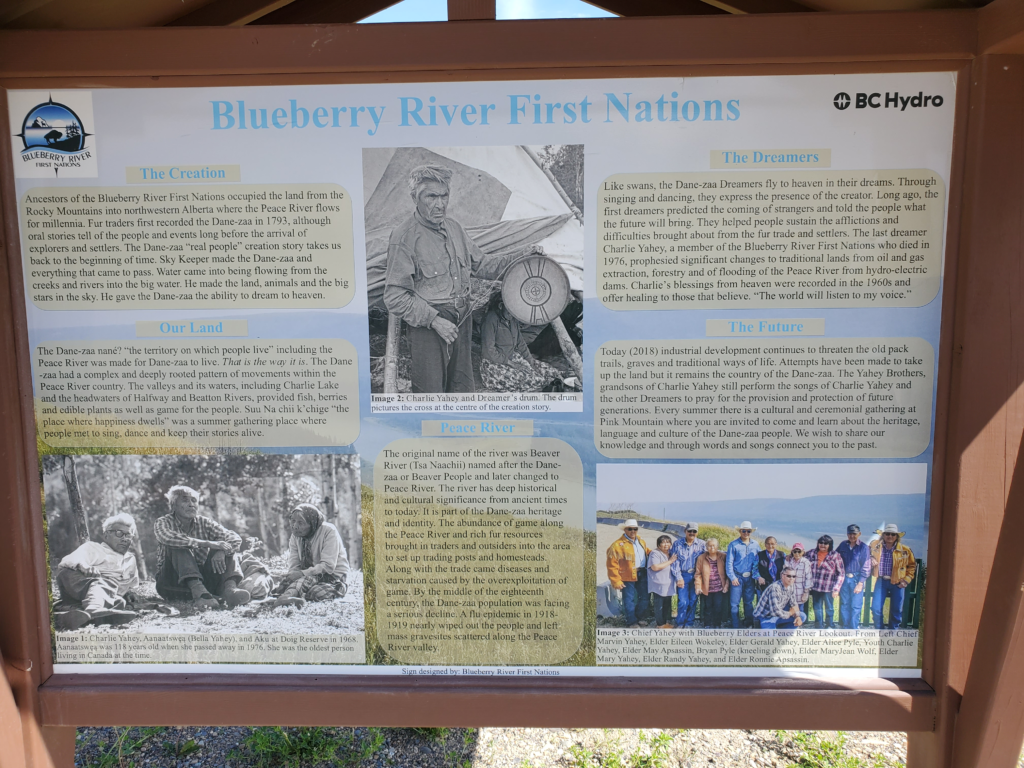

A bit further on I turn off toward something called the “Site C Viewpoint”. This turns out to be the public relations overlook for a large BC Hydro dam site. The parking area has nicely designed displays touting the indigenous heritage of the local tribe and paying lip service to its importance. Turn your head and you see an enormous construction project transforming square miles of forest into concrete, which will then flood a large valley. I’d say the indigenous people are sacrificing a lot.

I proceed northward into rainy weather and less populated terrain, the road undulating over gentle ridges and bridged across the low lying rivers.

There aren’t many people, but lots of roadside wildlife. I first spot a brown bear, shy enough to amble into the forest when I stop the car, but over the course of the day I see four sets of black bears and several large porcupines, all unperturbed when I stop within yards of them.

As evening sets in — by the clock, not by any approaching darkness — I stop in Fort Nelson BC for gas. The station insists on full service, a nice change of pace from pumping my own fuel. It’s time for a rest so I drive to the town’s A&W intending to buy a drink and use their internet service. A sign on the door says that due to staff shortages they are only serving at the drive through and I find that closed a few minutes ago. I decide to lurk in the vicinity and use their internet from my car once they close down, but even that doesn’t work because their cleaning person never leaves and apparently sleeps there. Eventually, I pull up anyway and connect, but the next frustration is their outdoor AC receptacle doesn’t work so I can’t charge my laptop.

Throwing up my hands, I drive to the adjacent, deserted car wash and successfully plug into their outdoor receptacle but, of course, I’m now a little too far to pick up A&W wi-fi. I give up and go to sleep while the laptop tops up. It’s been a long day on the road.