Prior post: https://blog.bucksvsbytes.com/2023/10/23/road-trip-europe-ii-23-10-16-getting-high-in-the-spanish-pyrenees/

Monday evening, shortly before dark, I arrive at my hosts, who live in the intriguingly named “Casa de la Presa” (The Dam House). As instructed, I walk across a suspension foot bridge and find myself in a set of channels, gates, and small dams. Wending my way along and across the works, past “Authorized Persons Only” signs, I come to a charming two-story house adjacent to the waterways and nestled under a towering limestone cliff.

[NOTE: Some displayed images are automatically cropped. Click or tap any photo (above the caption) to see it in full screen.

As I enter, I’m welcomed by my hosts, Maite and Jordi, who warn me their home is full of bones – and indeed it is. Skulls on shelves, skeletons on tables, disarticulated animals in file drawers, bones everywhere!

After settling into my room, I naturally ask about the story of the house. I’ve resolved to speak Spanish here to improve my comprehension and vocabulary but it quickly becomes obvious we have way too much to say to each other so, without comment, we lapse into English most of the time. It’s quickly apparent that Maite’s favorite English expression is “Super cool!” and everything we talk about for the next few days is so designated at some point.

Briefly, the works used to have a damkeeper but they were automated long ago and the house fell into disrepair during over 15 years of abandonment. This is not a dam that holds back a reservoir, but one that regulates stream flow entering a covered ditch which channels the water into a penstock miles downstream that powers three hydroelectric turbines. Maite and Jordi approached the power company 20 years ago and asked to be allowed to renovate the house and live there rent-free. This would benefit the company by creating a presence on the property and having unexpected problems reported promptly.

The arrangement formalized, they began renovating, at great effort and significant expense. The house has absolutely no vehicle access. All material must be carried or wheeled by hand cart from the highway and is limited to the narrow width of the walkway. They said getting the refrigerator in was particularly challenging. The power company supplies their electricity and water without charge and the lack of rent makes it a unique and cheap home. Privacy is assured because in addition to the pedestrian limitation, anyone entering the area without an invitation is trespassing.

Maite is an accredited archaeologist and Jordi plays a major role in digging, finding artifacts, and preparing them. They primarily study Neanderthals and have expanded the accepted age and cultural level of that extinct species. Much of that work is done through examination of animal bones, e.g. by searching for evidence of tool use on them and the relationship of bones to firepit charcoal, which can be dated by various methods.

The archaeology digs alone don’t explain the plethora of bones in the house. Bears have been re-introduced back into the Pyrenees. Since the initial Slovenia transplants were released, the species has thrived. To keep the peace, farmers and ranchers are compensated for any livestock killed by bears. The lucrative payments naturally give the farmers a perverse incentive to claim any dead animal is a bear victim. To reduce cheating, the government contracts with Maite and Jordi to investigate the deaths and determine which are legitimate bear kills, rather than other causes such as dogs, natural or accidental demise, etc.

They examine the carcasses, then boil them to clean off the meat, and study the bare bones for damage characteristic to bears vs other predators. If they can show bears were not involved, the claimant receives no compensation. Jordi has a small shop under the cliff and away from the main house where he boils carcasses for 20 hours at a time. I didn’t make it into the shop but I’m sure this is not neat and odorless work.

He has also wired together many skeletons into high quality re-creations, which reside in the house and outdoors. The two of them literally live in a museum.

After some hours of conversation, I hit the hay and sleep to the sound of falling water outside the window.

Tuesday morning dawns cloudy with the threat of rain. There’s a small village high up on the far side of the valley that Maite says can be reached by trail.

Normally, she would accompany me on such excursions but, tragically, she has a herniated spinal disk and has been in severe pain for many months. Since I suffered two long periods of identical issues 13 and 28 years ago, I’m one of the few people that fully understand her agony of chronic back spasms and sciatica. Thanks to our shared experience, Maite and I quickly develop a common bond of misery empathy. Her doctor has finally opted for surgery and Maite carries her phone with her every minute, waiting for the call that it’s been scheduled. All the while I’m there, she doesn’t get that call, but I reassure her repeatedly that my two operations were both long lasting, overnight, miracle fixes.

I think about hiking to the village but it’s raining intermittently and, as I’ve warned countless people, including my son who does it frequently, hiking alone can turn what, with a companion, would be a minor mishap into a fatal accident. The threatening weather is enough excuse to just hang around and enjoy the dam property.

Reinforcing my caution, Maite tells me a horrible story. Some time ago she was hiking alone on one of the local trails. During a descent, her foot slipped out from under her and she slammed supine to the ground, one knee shattered with multiple breaks but, fortunately, not a compound fracture (i.e. no exposed bone piercing the skin). Completely immobilized and in excruciating pain she managed to extract her phone. She knew that many portions of the steep terrain have no cell service and she was desperately hoping she was not in one of them. In the cool weather, she was inadequately dressed for spending hours on the cold, damp ground and knew she was likely to die of hypothermia without prompt aid. Fortunately, her phone was in range of a tower and, additionally, her brother is part of a mountain rescue squad. She reached him and he brought assistance in the shortest time possible.

Although this undoubtedly saved her life, she needed very extensive surgery to put her knee back together with metal screws, straps, and bone transplanted from elsewhere in her body. About a year ago, with the knee healed but chronically painful, she had all the metal removed, I imagine against medical advice. She is now told to abstain from a number of athletic activities forever. Five seconds is all it takes to permanently change your life.

I spend some hours prowling the grounds, noting the engineering of the gates, dams, and sluiceways. At one point, I hear a motor come to life and an automated rake on a timer scrapes floating leaves off one of the trash racks keeping debris from going downstream to the turbines.

Maite and Jordi are quite self sufficient, eating a lot of local products, their own garden-grown vegetables, and eggs from their three chickens. Every meal I eat here is tasty and unusual. You could easily call their unique living situation paradise, although one requiring a lot of hard work.

My contribution is duck paté. I found some at a Girona supermarket for what turned out to be a mismarked price. It was such a bargain, I bought six packages and I’ve been carrying it in my cold bag and eating paté sandwiches every day since. I arrived here with one package left and Jordi really enjoys it, so I leave it all to him.

This evening, I get a surprise. Maite is also a rock and roll singer/guitarist and she has invited a younger friend, Natalya, to come over. The two of them are going to do a concert just for me! Keep in mind that all the hospitality Maite offers me is done by someone who can’t sit or stand for more than a an hour or two before the pain reaches a level where she’s forced to lie down. That’s the kind of crazy shit that I might attempt, too, but normal people would just say, “I’m in severe pain, so you can’t visit.”

They do more than 10 songs, among them Pink Floyd, Dylan, John Denver – a broad range of styles. No one has ever done that for me, certainly no one I just met the day before. It’s a great evening, full of laughter as usual. I try to introduce them to some of my favorites – You May Be Right, Bad Case of Loving You, The Marvelous Toy – but they aren’t as enthused as I am.

In this YouTube video, Maite is playing bass and Natalya is singing: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QkbtfYI3YnE

Eventually, the delicious food is mostly gone, Natalya goes home, Maite is forced to get horizontal, and the evening ends. What a great time – super cool!

I think these photos convey what a good time we were having

Wednesday morning, it’s raining continuously and the sky is very dark. Once again, I decide to postpone hiking and stick close to home. It’s a good day to write, send out hosting requests, and take occasional forays into the yard during the short rain free intervals. When Jordi comes home from his day job – trucking waste water between various local treatment plants – we have sourdough pancakes, which is one of the go to meals I prepare as a token of appreciation for hosts. I had started the batter two nights ago and now it’s very frothy. We eat some pancakes with a savory vegetable mixture and others with sweet toppings, American style. They must have enjoyed them because they’re all scarfed down pretty quickly.

I walk out along the path to get a little outdoor break and see the water flow is now so heavy that the three foot high waterfall that separates the holding pond from the sluiceway has disappeared because they’re both at the same height. A lot of rain today.

The three of us spend more hours talking archaeology, bones, politics, evolution, and attitudes for life. I tell Maite that I characterize myself as a cheerful pessimist, in the sense that, yes, human society is circling the drain but I’m not going to let it ruin my day. Her retort is that she’s a cheerful optimist in that she is confident humans are about to relinquish their dominant, powerful role on the planet and make much needed room for the evolution of other species, which will be, of course, super cool. We both agree that technological progress has far outstripped the excruciatingly slow process of evolution. We’re wielding planetary scale tools with what is, essentially, still a paleolithic brain. Also, that the mortality rate is 100%, medical statistics notwithstanding. Everything dies.

With that, the evening ends. About 1 AM, an outside noise wakes me up. Looking out the window, I see two utility employees under floodlights on the catwalks, adjusting various water gates and removing debris, doubtless to forestall flooding problems.

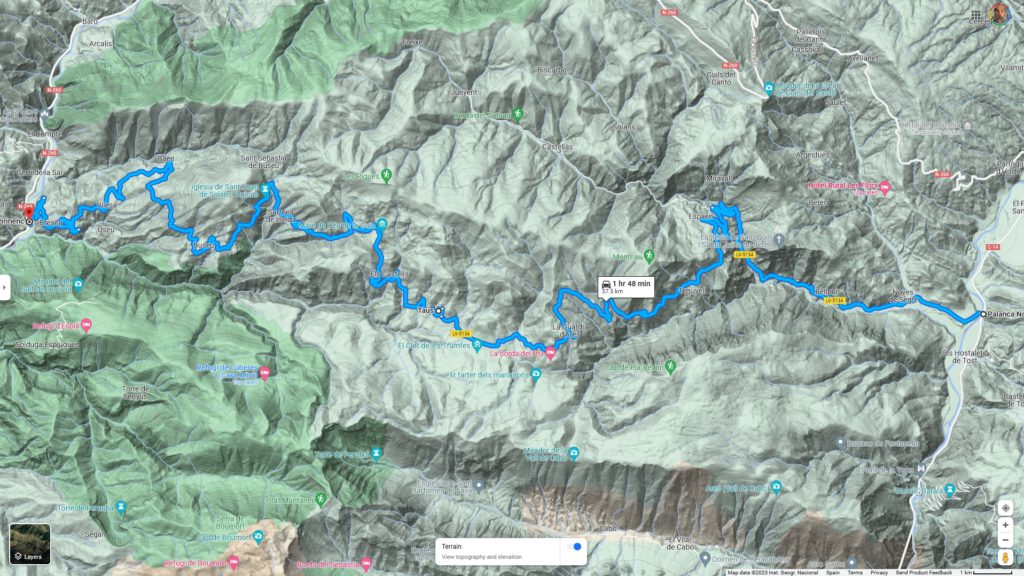

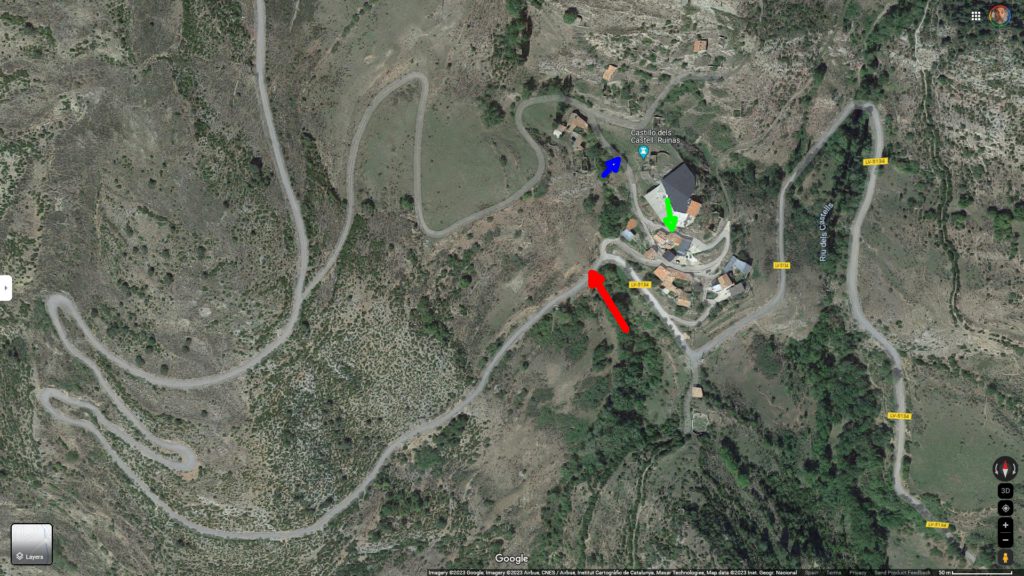

Thursday morning, it’s still raining but this is my last day before moving on so I’m determined to go sightseeing and hiking. Not far to the north is Aigüestortes i Estany de Sant Maurici National Park, The first part translates in Catalan as “winding streams” and the second as Lake Saint Maurice. As these are the only two road accessible areas and are an opposite sides of the large park, I’m going to circumnavigate the whole thing to visit them both. Leaving the dam, I head east on yet another of those narrow, winding, paved roads, past tranquil Lake Montcortés.

I do manage to get photo of a kite flying above me during a stop. At high magnification and without a tripod it’s mediocre at best but it does show the kite’s characteristic forked tail.

I then pass dramatic rock ridges into the deep valley of the Noguera Pallarasa River.

The road follows the river upstream through a very deep and narrow canyon through that rock

and then many miles further up a slightly wider valley. The river is quite tame yet I pass puzzling signs advertising white water rafting.

Apparently, during tourist season, an upstream dam releases voluminous water during the day for rafting and then almost shuts the river off at night. I make an arbitrary turn up a steep, dead end road. The village at the top is disappointing as it’s vacation condos built to look old, but I do find a very interesting stone barn on the way up.

The scenery along the valley is quite nice except for Spain’s habit of placing electric transmission lines, often multiples, on prominent slopes, disturbing the view for long stretches.

I reach the turn off for the national park and drive up a small road to a much higher parking area. It’s been raining off and on the whole way but I decide to walk up a 2.5 mile trail to the park’s namesake lake.

For a short while the trail is a wheelchair accessible wooden walkway and then becomes a well-engineered stone path steadily ascending up the valley.

Unfortunately, on a wet day like this, the beautiful construction of wood and flat stones becomes very slippery and I have to take care not to lose my footing, even though I’m wearing hiking boots. I have Maite’s accident firmly in mind.

The forest is principally fir and pine, with a few very large specimens. Deciduous trees have a hard time on this slope.

A paved road parallels the trail, which always annoys me. It’s much less fun hiking somewhere you can drive. That’s why I’ve never ascended Mt Washington in New Hampshire on foot. It’s depressing to slog thousands of vertical feet up a brutal trail only to find a big parking lot and underdressed tourists eating in the restaurant.

In this case, though, the road is for authorized vehicles only and is above the trail, so the only disturbance is the noise of an occasional passing car. The latter part of the walk is a steep dirt road and I arrive at the lake with some additional uphill effort. Except for three school groups going down as I ascend, the area is pretty deserted due to the weather and time of year. Tall mountains surround the lake and there’s a roofed shelter to offer some respite from the light rain.

My stamina for level hiking hasn’t changed much over the past 20 or 30 years. I can still go a long way under modest backpack load. Ascent, though, is noticeably different these days. My uphill pace has slowed and I make a lot more 5 second rest stops than I remember, to let my leg muscles remedy their oxygen deficit. It’s not nearly as bad as 15 years ago in Peru where, on the steep, high altitude trail it was step, step, step, breathe, breathe, breathe — why the hell isn’t there more oxygen up here! That wasn’t due to age.

After soaking up, literally, the views, I head back down. The rain gets heavier and constant so the walk down is soggy. Son, Eric, has loaned me a pullover raincoat and today I really appreciate it. My formerly trusty, zippered LL Bean rain jacket has over the last 2 years failed distressingly – all the seam sealing tape has come unglued making it quite leaky. I forgot to replace it before I left the US and I would have been soaked to the skin today without Eric’s substitute.

The trail is an out-and-back, so to make it into a loop, if only a trivial one, I choose to walk the longer paved road once I encounter it. I don’t meet any humans or animals on the way down and the steady rain makes for a very pleasant descent despite the pavement. Since I didn’t wear my rain pants, the runoff from the rain jacket has soaked my blue jeans but for the distance and weather, there’s no danger of hypothermia, so I don’t care.

Back at the car, it feels good to have taken even a short hike. Again navigating the narrow, paved road back to the highway — this time in heavy rain, I continue my counterclockwise drive around the park while a 30 minute blast of the car heater dries my pants in short order.

The road goes up over a pass and past a summer-closed ski area. At the top there’s a monument to the first snowblower used there – kind of quirky.

Descending back into a valley of ski resort towns, I pick up two Spanish young people hitchhiking at a bus stop. As we’re talking in the car, the woman asks why I picked them up because no one ever does. I explained that I’ve traveled many thousands of kilometers “a dedo” (on my finger, i.e. thumb) so I always return the favor. She asks why I say “thumb” and I have to explain that in the US you stick out a thumb to solicit a ride. When I later relate this to Maite, she’s puzzled at the question because she says the same technique is used in Spain. The couple work in the ski industry in the winter and semi-starve the rest of the year. They ask me to drop them off in the town of Vielha. I ask them if that means “old”, since in various Romance languages the word is “velha”, “vell”, “viejo”, “vieille”, etc. They, Castilian Spanish speakers, say “no”. When I get home, Maite looks it up and finds it does mean “old” — in Aranese, yet another obscure Romance language that’s spoken in that area of Spain. I’ve never even heard of it and it’s so obscure that Google Translate doesn’t handle it.

Coming around to the west side of the park, I encounter more tunnels, as has been common in Spain. In fact, it appears the Spanish like tunnels as much as Swiss, whom I’ve described in the past as building tunnels the way other people change underwear. None of the Spanish tunnels match the absurd lengths of Switzerland’s longest ones, but some are miles long. In the US, tunnels are a last resort. Highway engineers and contractors much prefer to remove enormous portions of a mountain to build a straight, level road rather than drill through it.

Still in heavy rain, I turn off up a valley to the Aigüestortes area. Visibility is very limited by the low cloud ceiling but the excursion is still worthwhile. I can’t get to the “winding stream” portion, which is beyond the end of the public road. In fact, the gate is closed, not just to cars, but to all entry. I suspect this is due to dangers related to the severe weather but there’s not a soul around to ask. The heavy rain has made the steep stream that drains the valley into a torrent with lots of water flowing over the rocks – very pretty and impressive.

The other interesting feature is boulders, massive ones at the base of the steep canyon walls. Some of these are much larger than a house, bigger than any I’ve ever seen. The lack of detectable scars on the forested slopes above make me think they are enormous erratics, pushed and then deposited by long ago glaciers.

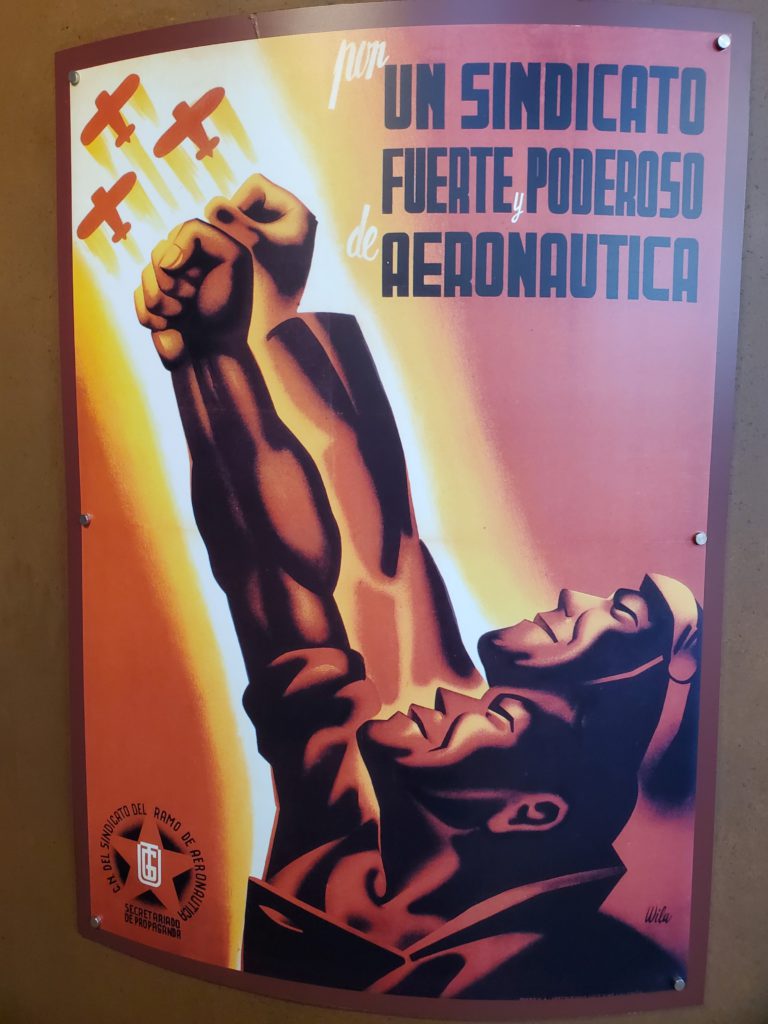

The ride back home is uneventful. At a gas station, I overhear two very soggy motorcyclists speaking in German, so I ask where they’re from. One of them is indeed German, but the other is German-raised but returned to Catalunya – another example of a family forced out of Spain by Franco-era repression.

We have several minutes of pleasant conversation before I continue on. Only 200 feet further,my phone rings and I pull into a truck parking area to answer it. It’s Susan – our oil furnace, which has been acting up recently is now completely unwilling to run. In the past this has been due to a failed flame sensor, which tells the control unit that the furnace has indeed ignited and does not need to be shut off to prevent accumulation of unburnt fuel. I ordered a sensor last week and it has arrived. Our friend, Vernon, is there to paint our outside deck and he installs the sensor while on the phone with me. The furnace still fails to stay ignited and after each shutdown smoke is being emitted from who knows where. We agree that professional help is needed and I spend a long time on the phone with the fuel company arranging an emergency service call. They agree to come in the next few hours, so the problem is now out of my hands, except for the probably absurd expense.

By now, darkness has set in for the last 17 miles of my drive home. It turns out that much of the road, despite being a national highway, winds severely and narrowly along a sinuous river canyon, not to mention two one-way sections controlled by alternating traffic lights. The nighttime, rainy drive is pretty challenging but far less than it could have been because the road is very well marked by reflectors, giving me good visual clues as to the approach of the next blind curve. I don’t see another car the whole way. Apparently, Spaniards all shelter in place during storms. After parking the car, a last rainy walk across the suspension bridge brings me safely home to Casa de la Presa. The waterways are still very full but the power company adjustments are now dumping more water into the stream bed so the sluiceway is a bit below its maximum capacity.

Maite is co-author on a journal article regarding taphonomy. Yes, it’s a new word to me, too, referring to the study of how organisms decay and become fossilized or preserved in the paleontological record. This article is discusses experiments with using artificial intelligence to classify the origin of various bone markings. Another author has written the draft in English, Maite has already edited it for errors and English usage, and she would like me to go over her version and put it into grammatic and natural American English. I’m happy to take on this challenge and agree to do it in the morning before I leave. With that, I say my heartfelt goodbyes to Jordi since he’ll be at work when I leave tomorrow and head up to bed.

Friday morning, I cook up the last of the pancake batter for breakfast (waste not, want not) and attack the journal article. I come up with a dozen or two minor edits regarding British spelling, Latin/English consistency, noun/adjective and singular/plural agreement, acronym definition, comma/apostrophe usage, and some confusing phrasing. Maite’s written English is very good but she greatly appreciates and adopts my edits. That finished, she and I say very reluctant goodbyes. I again wish her a quick and total cure of her back problem and my hope she overcomes her admittedly irrational fear of flying so they can visit us in New York. I lug my stuff across the walkways and bridge to the car and I’m off westward.