When I arrive at Casa Crescente on Friday afternoon in the little village of Boca de Huérgano, I find a small bar and very nice rooms upstairs, again for very little money. There’s no refrigerator but it’s cool enough for me to store my perishables on the window ledge. I ask the bartender about dinner and out of his rapid fire answer, I catch “homemade” and “8:30”. I occupy myself in the room for a few hours and at the designated time I go downstairs. The bar is full of locals engaged in loud conversation and drinking beers.

[NOTE: Some displayed images are automatically cropped. Click or tap any photo (above the caption) to see it in full screen.

My Spanish comprehension isn’t nearly good enough to insert myself into any of these groups, so I step up to the bar and say, “Comida?” (food). The bartender hands me a beer and a square of some very tasty baked good. The food turns out be not a meal but one of these homemade tidbits from a tray. Disappointed in the quantity although not the taste, I down my $1.60 dinner and head back upstairs. I know they serve breakfast and lunch so I have no choice but to make the snack do until morning.

I’m going to spend Saturday circumnavigating and probing the park, so I dress for the cold and wet. Breakfast is very good and extremely reasonably priced and I’m soon off. As I head out in a clockwise direction, my first point of interest is the Riaño Reservoir, a miles-long, triskelion-shaped basin whose water level is so low that much of the pre-impoundment road and bridge system is exposed.

As I turn north, the low ceiling hides the upper slopes of the Picos except for brief glimpses. Close up, I can see that my declaration yesterday of “termination dust”, while technically correct, was mostly an illusion. The very highest peaks do, indeed, have some snow at the top but the mountains are composed of white limestone which, seen yesterday from 10 miles away through rainy skies, I mistook for large areas of snow.

I turn off the circumferential road into one of the two park accesses. This road winds almost 14 miles into the central mountains, getting successively twistier, narrower, and steeper until it ends at the hiking base town of Caín along the Cares River. From here, a beautiful trail is said to wind deeper into the mountains. Sadly, between the inclement weather and lack of a hiking companion, I don’t even seriously consider the route. The drive in, though, is spectacular through enormous limestone mountains. I’m not sure I’ve ever seen so much rock landscape. It’s almost unbelievable that the Pyrenees and Cantabrian mountains were all sea bottom.

The limestone has created a karst topography, with many cliffs, pinnacles, and caves throughout the two ranges. Limestone, made of geologically compressed shells and other calcium remains, dissolves relatively easily, especially if the water is slightly acidic. This solvent property is the reason increasing CO2 levels are threatening the survival of marine invertebrates like corals, molluscs, and crustaceans. Significant acidity prevents the chemical reactions that build their calcium based exoskeletons. Limestone erosion often happens in a geologic eye blink. Today, the rock still dominates with trees confined to the areas where they can survive. Rather than futilely attempt to describe the landscape further, here are some photos taken along the route:

Along the way, I pass a stone structure used as far back as the 17th century as a wolf trap. Taking advantage of wolf pack behavior, villagers with spears were stationed in a pattern across the narrow valley that forced a pack of wolves into a spiral pattern that ended in the stone enclosure, where they could be slaughtered for meat.

After reaching the last driveable few feet of road in Caín, I work my way back to the highway, turn north and start looking for a meal. I really wanted the lunch back at Casa Crescente, but since it’s only served from 1:30 to 3:30 I was quite sure I would miss it. Since every restaurant serves a daily lunch, though, I know it’s not a problem. As I enter the village of Oseja de Sajambre, the streets are full of cars and people. I drive past the village and find the first unused curb parking spot, then walk back about 1500 feet. I’ve happened here on feria day, and people have come from miles around to sell and buy everything you can imagine.

Livestock is a major portion and there are horses, sheep, cows, goats, and pigs in various pens and corrals, all being watched over by children with long rods used to herd the animals and all being gawked at by prospective buyers.

Food and clothing is also being sold so its a very festive, busy day and many people have been clearly looking forward to it.

Since I’m there at peak lunch hour and every eating establishment is mobbed, l wonder how hard it will be to get a table.

I squeeze through the bar crowd at one place and realize that most of the clientele are drinking beer and eating snacks. The dining room is not overly crowded. My two lunch courses are beans and cod and a plate of very tender goat with the obligatory, for me, flan dessert. The food is very good and I’m sharing a table and conversation with a young Spanish man who’s on a one day excursion here from his coastal home to enjoy the market. The lunch back at my hotel was posted at only $12 and I assume, mistakenly as it turns out, the price at other restaurants will be in line with that. When I get the check, though, the price is $21, a big and unexpected difference but not a tragedy.

Continuing my drive around the national park, frequently still through dramatic and impressive canyons,

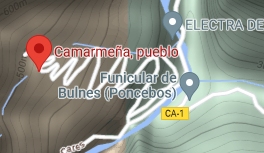

I enter the other spur to its interior. This one follows the same Cares River upstream to the north end of the hiking route from Caín. The shorter road isn’t as impressive as the earlier one but its extreme end is a village named Camarmeña, impossibly perched on a slope high above the valley accessed by a steep, winding road dicier than almost anything I’ve seen to date. I have to use first gear all the way up, and most of the way back down.

Although the light is fading, I try an alternate route out of the park displayed by Google Maps — anything to avoid a backtrack. Using tiny roads is always chancy because many of them are closed to unauthorized traffic. In this case, I read on an earlier sign that there are no public routes through the park. But, what the hell, Maps says it works. I drive up and up and up a paved road to the high country for 10 miles and at the turnoff I need, sure enough, the “Authorized Vehicles Only” sign is prominently displayed. The chances of getting in trouble for driving it are tiny, but if I were to break down along the way that trouble might be unavoidable. Plus, I have no idea that the road is passable all the way across to the main highway. One locked gate and I’m done.

Reluctantly, I turn around and twist my way back to the river. By the time I reach it, last light is fading and the rest of my long drive is in the dark. On the main, national highway which has long stretches of one and a half lane pavement, I’m behind a large bus which must painstakingly slow up to allow the frequent oncoming traffic to get by. In addition there are 3 construction sites, deserted at night of course, with long, traffic light controlled, one way sections. At each light, the wait is 5-10 minutes for the green.

Finally, miles later the bus turns off and the road becomes more standard. It’s 9:30 PM by the time I return to my comfortable room, much too late even for the evening snack.

I leave Casa Crescente early morning heading back to the coast. I was looking forward to breakfast before I hit the road but the door to the bar is locked and a small sign says “Closed for Sunday rest day” so instead I go to a tiny nearby bakery and get something that looks like a tasty pastry. Unfortunately, it turns out to be filled with tuna fish — not at all what I had in mind. But as they say, it beats a poke in the eye with a sharp stick.

With pastry crumbs falling into my lap, I head up the highway to my next destination, the beach, port, and industrial town of Gijón.