Prior post: http://blog.bucksvsbytes.com/2021/08/02/road-trip-21-06-20-we-head-south-across-the-alaska-range/

[NOTE: Some displayed images are automatically cropped. Click or tap any photo (above the caption) to see it in full screen.

We’re up and driving by 6 AM, covering the last 10 miles of paved highway to Chitina (the second “i” is silent: CHIT-na). Before dropping down to the historic village, we skirt a series of picturesque rock cleft lakes.

It’s cold, windy, and raining but we stop at the Chitina Wayside to have breakfast under its picnic shelter.

Chitina has some interesting buildings from its long ago bustling past but, at least early Monday morning, very little activity.

We’ve been paralleling the Copper River, one of Alaska’s major salmon spawning routes, all the way from Glenallen, but we’ve rarely seen it from the road due to intervening terrain. Here, where the Edgerton Highway ends, we join the route of the old Copper River and Northwestern Railway. This prodigious engineering feat, completed in 1911, ran 200 miles from the coastal port of Cordova to the Kennicott copper strike, through forbidding terrain. The $25 million project cost paid off as the mine generated at least $100 million in profit before closing in 1938, when the railway was shut down but left in place.

One of the many engineering accomplishments was spanning the wide, fast, and variable flow Copper River just past Chitina. The rail trestle sustained severe damage every year, to the point where the railroad preemptively pulled up the track before the spring breakup, rebuilt the pilings after the floods, and replaced the track. After abandonment, the next flood permanently destroyed the structure in 1939.

In order not to strand residents along the rail line, the Alaska Road Commission assumed maintenance of the track and a 1930s aerial tram that allowed people and goods to cross the Copper River where the bridge used to be. Private companies ran rail-converted automobiles along the track.

As the tracks deteriorated, summer travel along the route became limited to bulldozers and other rugged equipment. After statehood, in 1959, the new highway department seriously considered converting the railbed to a McCarthy Road. Contractors pulled up the steel rails and made a very rough one lane jeep trail. It took until 1971 for the state to build a new, permanent highway bridge across the Copper River at Chitina — to this day it’s the only functional bridge along the river’s 300 miles. McCarthy’s few residents and others along the route were once again, however crudely, connected to the highway system. Well, almost. The road ended across the Kennicott River from the tiny settlement because there was no money to replace the washed out railroad trestle. A half mile walk punctuated by two hand operated tram cars across glacial rivers was the final segment of the journey.

This was the state of things when the McCarthy Road first caught my attention. I brought an old Jeep Wagoneer to Alaska when I arrived in 1975 but it was never reliable enough for the off road adventures of which I dreamed. I had renewed hope when I acquired my first Subaru in 1977. It was gaining popularity in the US but my 4-wheel drive DL wagon was still a novelty in Alaska. Detailed inquiries, though, convinced me it didn’t have the ground clearance necessary for the trip. As well, the remaining trestle crossing was so hair raising that many travelers were said to give up at that point and turn back. To my everlasting regret, I never attempted the 62 mile journey before I left the state. It would have been a great adventure.

Now is my delayed chance for redemption, although the road has been greatly improved to where any vehicle can make it. Leaving Chitina through an old railroad cut (it used to be a tunnel but the covering rock was removed after maintenance workers were killed inside by falling debris), the road curves down toward the long bridge.

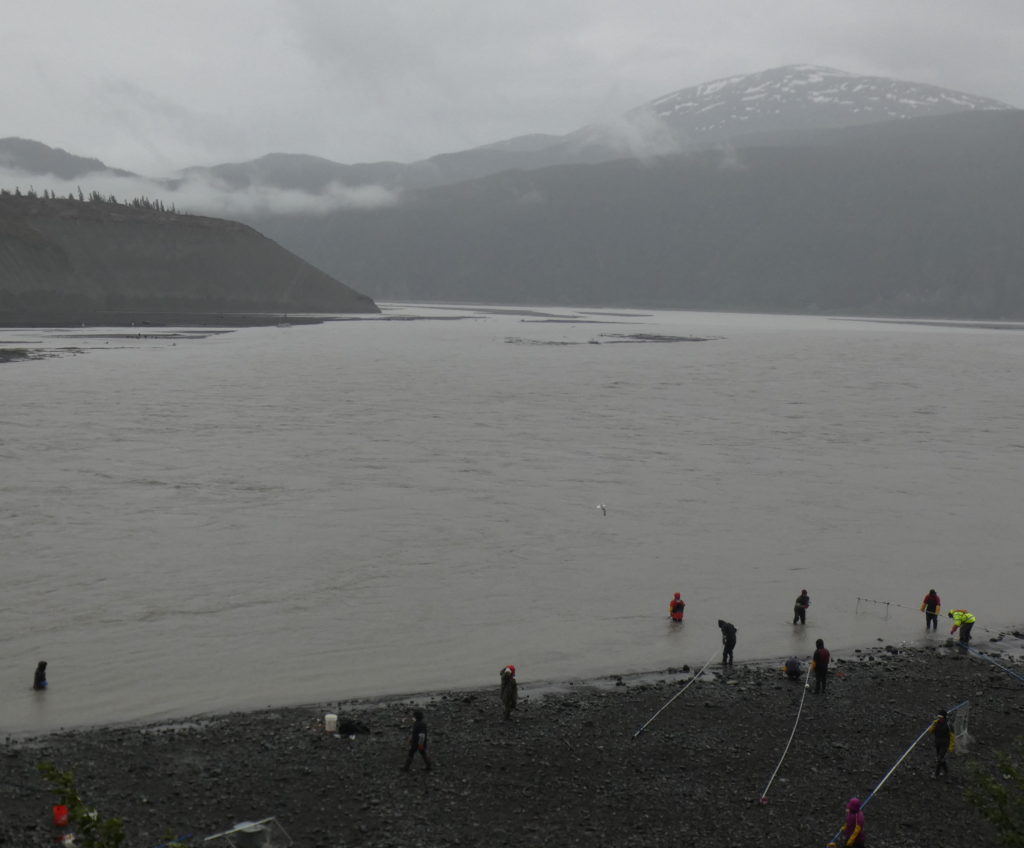

This is our first broad view of the Copper River in many miles. Some of the most prized salmon in the state are caught here as they swim upstream through the opaque water to breed in various small, clear tributaries.

The salmon are running and many people are trying to catch their limit, after which they’ll race home to clean, filet, and freeze them to last through the winter. City and rural, Anglo or Native, to many Alaskans the king salmon runs are a highlight of the year. Here on the Copper River, only two methods are permitted: a fish wheel (mostly used by Alaska Natives) and dip net (used by everyone). Both depend on the silty, opaque water to catch salmon blindly navigating upstream to spawn. If the water were clear, the fish would simply evade the wheels and nets.

Fishwheels are the more technological approach. A large wheel with baskets pointing downstream is anchored in the river. The downstream flow turns the wheel, whose baskets may scoop up salmon swimming upstream into their path. Dipnetting requires less elaborate gear: a large net at the end of a 10-40 foot aluminum poll and quality chest waders.

Dipnetting, however, takes skill and strength… and it can be fatal if mistakes are made. Dipnetters wearing waders walk downstream, chest deep, parallel to the shore, holding their nets perpendicular to it on long horizontal poles. They have to move fast enough for the net to billow out upstream instead of downstream where the current tries to push it. Any salmon coming upstream and running into the net may get tangled in it and be caught.

Picture the situation. You’re walking above your waist in near freezing, fast flowing, opaque water. Should you lose your footing and the river water overtop and fill your waders, you could be lost in a matter of seconds unless someone is right there to try to grab you. If your body goes under the surface, you’ll immediately disappear from sight while you’re weighed down and swept downstream.

At the end of each traverse, you walk up on the beach, remove a salmon if you’re lucky, and wade downstream again with net deployed. You have to really love salmon to be a dipnetter in Chitina.

Proceeding across the Copper River bridge, the road turns to gravel and we begin the 62 mile journey to McCarthy. A warning sign tries its best to discourage going further.

The road is built on the old railbed but it starts out uncharacteristically steep for a railway. How did trains make it up from the river? Not easily. Eastbound trains generally had to be split in two so the locomotive could pull the first half to the top, return downhill for the second, and reassemble the full train before proceeding.

As advertised, the road is in good shape. It’s wide enough for opposing traffic to pass although the shoulders are often several feet above the surrounding terrain. Let your right wheels go just a few inches beyond the road surface and you’re in serious trouble in the woods below the road — if you avoid a full rollover! Sure enough, along the way we pass two vehicles abandoned after just such a mishap.

Every so often, where the road is wearing down, we see evidence of railroad ties poking through the gravel. In the early years, accidents caused by driving over railroad spikes were not uncommon, By now, encountering one is very rare.

There are no services anywhere between Chitina and McCarthy — except for one flat fixer.

Sixteen miles in, we come to the Kuskulana Bridge. Here, the railroad spanned a 525 foot valley, 230 feet above the river, on an iron structure. Later, this was crudely converted for automobile use by installing parallel planks on the railroad ties as wheel paths with flimsy wooden “curbs” attached to the outsides. When they heard tires screeching against either curb, the driver knew they weren’t centered on the planks. This daredevil arrangement served for many years, but by all accounts it was a hair raising crossing.

More recently, the bridge has been converted to a safe one lane road with a wood plank driving surface and guard rails. As we arrive, though, traffic is blocked in both directions while a bucket truck moves slowly across with engineers inspecting the original steel substructure. We’re told this is the beginning of a project to build a two lane road across the former one track bridge. Let’s hope they know what they’re doing.

After about an hour, the inspection is completed and normal one way at a time bridge traffic resumes.

As I mentioned, the current road is no great challenge and we proceed slowly along, stopping to gawk at whatever looks interesting.

About halfway along, the road leaves the old right of way to bypass the Gilahina trestle. Long abandoned and visibly sagging, the 880 foot long, 90 foot high, wooden trestle’s main claim to fame is being built in just 8 winter days in 1911, using half a million board feet of timber. I doubt any construction crew today could match that feat.

As we approach McCarthy, it becomes obvious there’s no public land along the last portion of the road where we can sleep in the van. The one National Park Service trailhead is clearly marked “No Overnight Parking”. Our choices are to pay a lot for a private campsite or pay even more for a cabin. We decide to splurge on the latter and after a number of inquiries at places with no vacancy or no human beings, we find Aspen Meadows B&B. The owner is kicking back after hosting a large group but she graciously offers to forego her rest and clean up one of the cabins for us. We accept her offer and agree to come back in the evening after spending the day in McCarthy.

Driving back to the end of the road, we see that reaching the village requires parking in the private lot and walking across the modern footbridge. It crosses two channels of the Kennicott River and was built by the state highway department in 1997 to replace the two hand powered aerial trams used for the prior 15 years. Although the bridge is prominently marked “No Motorized Traffic” ATVs and motorcycles use it freely, along with bicycles and pedestrians.

From the far end of the bridge, it’s a short walk to town, so we pass up the van shuttle offering transportation. There’s an exhibit of a kluged together, one of a kind truck built in the 1950s (long before there was a vehicle road) and nicknamed the Rigor Mortis. Its owner used it locally for about 35 years. You know what they say, “Necessity is a mother!”

A short walk past old railroad relics and overgrown structures brings us into McCarthy. The community sprung up as a Sin City during the mining era, 1911-1938, to supply all the services prohibited on the property of the nearby Kennecott Mine — alcohol, gambling, and prostitution. When the mine closed, McCarthy became a virtual ghost town until young people seeking adventure and alternate lifestyles started arriving in the 1970s.

The creation of Wrangell-St Elias National Park in 1980 slowly allowed McCarthyites to make a living from adventurous visitors arriving on the rough but passable road. Tourism businesses were started and the summer population grew. Only a couple of dozen people stay through the winter, but today most of the remaining original buildings are in use as hotels, restaurants, and stores. McCarthy is still definitely off the grid, but nowhere near as much as before.

As an “end of the road” locale, the town has borne the brunt of some tragedies perpetrated by disturbed characters at the end of their road. In winter 1983, a part time resident suddenly went on a shooting spree, killing 6 and wounding 2 of the 23 people in town.

With the nearest police 100 miles away by air, the killings were only stopped when one of the wounded managed to knife the murderer, causing him to leave the area on a snowmachine before being apprehended late that day.

In 2002, a patriarch and 10 of his children unexpectedly arrived in town in two pickup trucks. For anyone to drive to McCarthy in January was highly unusual, much less a big group in two open trucks. This was the Pilgrim family looking for a new home away from bad influences. The deeply religious group made a good impression in McCarthy and in the spring they returned full strength to take up residence, 2 parents and their 15 children. Over time, the initial support of other townspeople weakened. The family operated almost as a cult. The father, known as Papa Pilgrim, prevented his children from socializing with anyone so as not to have them ruined and was the face of the clan to the outside world. He ran afoul of the Park Service, often seen as the enemy by rural Alaskans but attitudes toward the family gradually turned mixed. The culmination came in 2005 when, despite their isolation from other townspeople, a family blowup exposed that for many years Papa had brainwashed and terrorized his wife and children and was having an incestuous relationship with a teenage daughter. He was sent to jail and died in 2008, leaving his giant family to figure out a new life for themselves after years of trauma and without his domineering presence.

We stop in at a bakery/gift shop. Although their food offerings are almost non-existent, we have a long conversation with the young woman working the counter. Like most people in town, she’s here only as a summer job and will return Outside (the Lower 48) long before winter.

We decide to have dinner at one of the two restaurants, sitting outdoors in the cool air. The food is quite good but, understandably, expensive in this remote location. For dessert, we buy the 2 cinnamon buns still on the bakery shelf. Nibbling on them as we walk down the road, we determine the friendly atmosphere is way better than the product.

At the end of the street is the old railroad station, now the McCarthy museum. The volunteer inside is helpful in interpreting the exhibits and artifacts. It’s what I call an “attic museum”, a very modestly curated collection of items, photographs, and clippings haphazardly dredged up from various locals. Still quite interesting, though, if you take the time to study the pieces and ask questions.

After checking out the remaining few yards of the street, including a period hotel and the world’s most unsatisfying grocery store, we walk back to the footbridge.

Retrieving the van, we drive the few miles to our pleasant cabin. Tomorrow will be our major sightseeing day in the area, so we call it an evening relatively early despite the endless daylight.