[NOTE: Some displayed images are automatically cropped. Click or tap any photo (above the caption) to see it in full screen.

I’m up early, for no particular reason. My Subaru parts won’t be available until afternoon. The streets outside the hostel are quiet, the demonstrators having gone home to sleep.

I’m hoping to head back to Mendoza today, but the chances of pulling that off are slim. The last bus leaves at 1:30 PM and my parts aren’t promised until 2 PM. I’m going to check out of the hostel and get to the store at around noon, hoping they arrive early enough to let me catch that bus. My drop dead time for leaving the store, parts in hand, is 1:00 PM, so I’m clutching at straws.

I go downstairs to look over the optional $7 breakfast the hostel offers. There’s plenty of food and it’s nicely presented, but most of it is artificially sweetened fruit drinks, coffee, and South American pastries and breads. Although this is standard fare, I find all of it fairly unpalatable so I go out and buy breakfast items and sit in the kitchen eating. What I buy isn’t any better than what they’re serving, but it’s cheaper and I have a liter of cold milk with which to wash it down. I check out, realizing that I’ll most likely be back this afternoon. As I’m preparing to spend a couple of hours in the lounge researching and writing, an emergency message comes in from Susan. Somehow, the cell phone of Ines, our landlady of the moment in Mendoza, has disappeared, probably stolen. She’s asking if I can buy a replacement in Santiago and bring it back with me. I’m imagining a comical exchange since Susan understands only certain Spanish words and Ines speaks no English whatsoever. Somehow the concept comes across and the task is now mine to execute in the short period before I have to head for the parts store.

I immediately interrogate the desk clerk as to nearby cell phone vendors. A consultation group of staff and locals is quickly formed to ponder my problem. To my extraordinary good luck, there is an appropriate store virtually around the corner, but is it open today when so much is shuttered? I walk out to the Alameda, which still shows the effects of yesterday’s demonstrations, locate the store, and find it open and bustling. Excellent fortune as it will most surely lock down in a few hours as the demonstrators return. A salesman latches on to me immediately and I explain what I need, a basic smartphone, not carrier-locked, and cheap. My luck holds and they have just what I need. Ines had suggested a price cap of about 70 dollars and this one fills the bill for less than 60. I text back and forth a couple of times to Ines, via Susan’s phone, and Ines says “get it!” I close the deal, being careful to get a sealed factory box and inspecting the contents before paying. What seemed like an impossible task at the outset has been accomplished in under an hour. Susan tells me the reserved Ines has lit up and is literally dancing for joy at the economical solution to her problem.

Buying a cell phone in Santiago during a lull in the demonstrations.

The $57 cell phone

Around noon, I shoulder my dead parts, cross the Alameda, and walk to the auto parts store. I ensconce myself on their waiting bench and do my best to cast significant looks at my salesman. Alternately pleading, impatient, and resigned expressions come pretty naturally to me, but it’s not as if he has any control over when the parts arrive. About 12:45, he tells me the delivery has come in. I excitedly queue up an Uber ride to the bus terminal, ready to trigger it the moment the metal touches my hand. The store paperwork and inventory procedures aren’t trivial, so I don’t actually walk out the door until 1 PM — probably too late. I call for the ride but it’s delayed in the heavy traffic and finally canceled. No go, but it was a long shot to begin with.

I walk back to the hostel, this time lugging 50 pounds of metal, both old and new parts, and check in to my same bunk .

I forgot to bring my leftover Chilean cash with me and I’m trying to avoid getting more so I’m limited to buying from places that accept credit cards. Normally, that’s no problem but in conjunction with the closures, my selection of stores is very limited. I’m thirsty and end up walking almost a mile from the hostel only to buy 2 liters of overpriced, bad tasting fruit drink. By this time, the demonstrations have resumed, so I hoof it back to the wide Alameda. The mood today is a bit less peaceful. Intersection fires have already been lit, there’s much more invective being hurled at the still-patient police, and vandals are being more brazen. At one point I see about 20 young men energetically rocking a 60 foot metal bus station railing out of its sidewalk foundations, perhaps to use it as a street barricade.

As I walk further west, I start to get whiffs of tear gas drifting in from out of sight. My eyes tear, my cheeks are stinging, and as I cross an intersection, the acrid burning smoke of a mattress fire starts to choke me.

I decide a fast retreat is in order and head down a side street at a trot. A noticeable number of others are taking the same action. One young man seeing me rubbing my eyes offers some water from his bottle to rinse them.

In the smaller side streets, the more peaceful protest still dominates. Every block is filled with groups of young marchers. Plenty of vulgar insults are being hurled at the police who have blocked off certain areas for their use, but again by a minority of the crowd. A frequent shout includes a word that sounds like “culio” which from the context is no compliment. The derisive term for the police seems to be “paco”. At one point a plastic water bottle is hurled at a group of standing police but elicits no reaction.

I have to say, though, that in two days an article in the Guardian (https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/oct/27/chile-hundreds-shot-and-beaten-street-protests) reports that hundreds of protesters have been severely injured by beatings and non-lethal, but still very dangerous, ammunition. It also alleges that Chile media are self-censoring scenes of police violence, so my direct observations don’t tell the whole story. I talk to more people, take more pictures, and marvel at how committed the many thousands are to invoking real economic change. The original incitement, the 3% transit fare increase has been long forgotten, and the government has actually rescinded it in a futile effort to appease the demonstrators.

The people I met and talked to are committed to change, but with my limited Spanish, I couldn’t fully comprehend their nuanced or complex stories. If you want to see professional reporting of protester interviews, I highly recommend https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/oct/30/chile-protests-portraits-protesters-sebastian-pinera.

Homeless amid demonstrations, Santiago, Chile, 25 Oct 2019

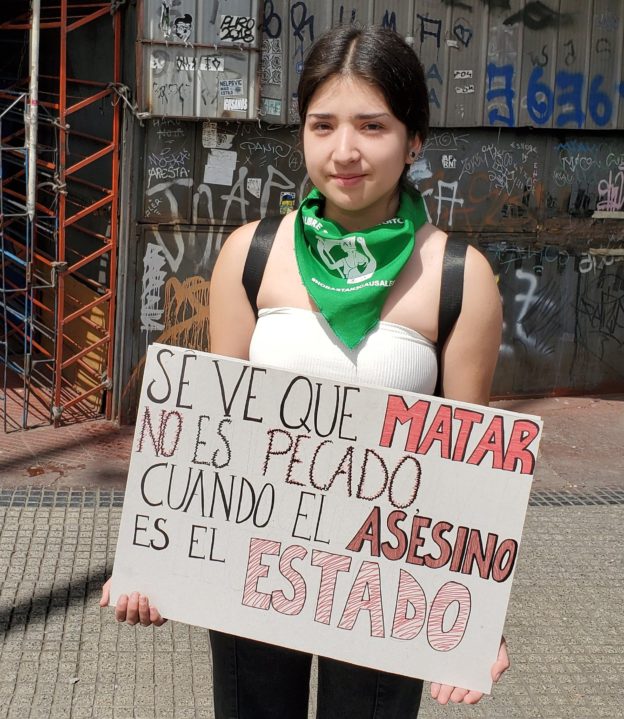

Demonstrators, Santiago, Chile, 25 Oct 2019

Demonstrators, Santiago, Chile, 25 Oct 2019

Demonstrators, Santiago, Chile, 25 Oct 2019

Demonstrators, Santiago, Chile, 25 Oct 2019

“Cacerolazo”, Santiago, Chile, 25 Oct 2019

Police, Santiago, Chile, 25 Oct 2019

Demonstrators, Santiago, Chile, 25 Oct 2019

Demonstrators, Santiago, Chile, 25 Oct 2019

Demonstrators, Santiago, Chile, 25 Oct 2019

As I mentioned yesterday, I shot a lot of photos. If you want to see more than the ones I’ve included here, the entire raw and unedited collection is at https://photos.app.goo.gl/pzeawM1WaUK9NhFg7.

I return to the hostel and sit in the lounge for a while researching and writing, but this isn’t much fun because I have only my phone to work on, rather than the laptop. Life is so hard. I give up and watch the live television news coverage which is reporting one million people in the streets. From the aerial photos of various cities, I can believe it. I sincerely hope these demonstrations lead to some fundamental economic changes but it’s not my fight and I have my own obligations. First thing in the morning, I have to get back to Susan and the Subaru in Argentina. I go up to bed and set the alarm for a 5 AM departure.