On a recent visit to Valencia, Spain, my host informed me of a literary “open mic”, Club Hemingway, in which he would participate. As a courteous show of support — and since it was being held in English –, I said I would attend to hear his piece.

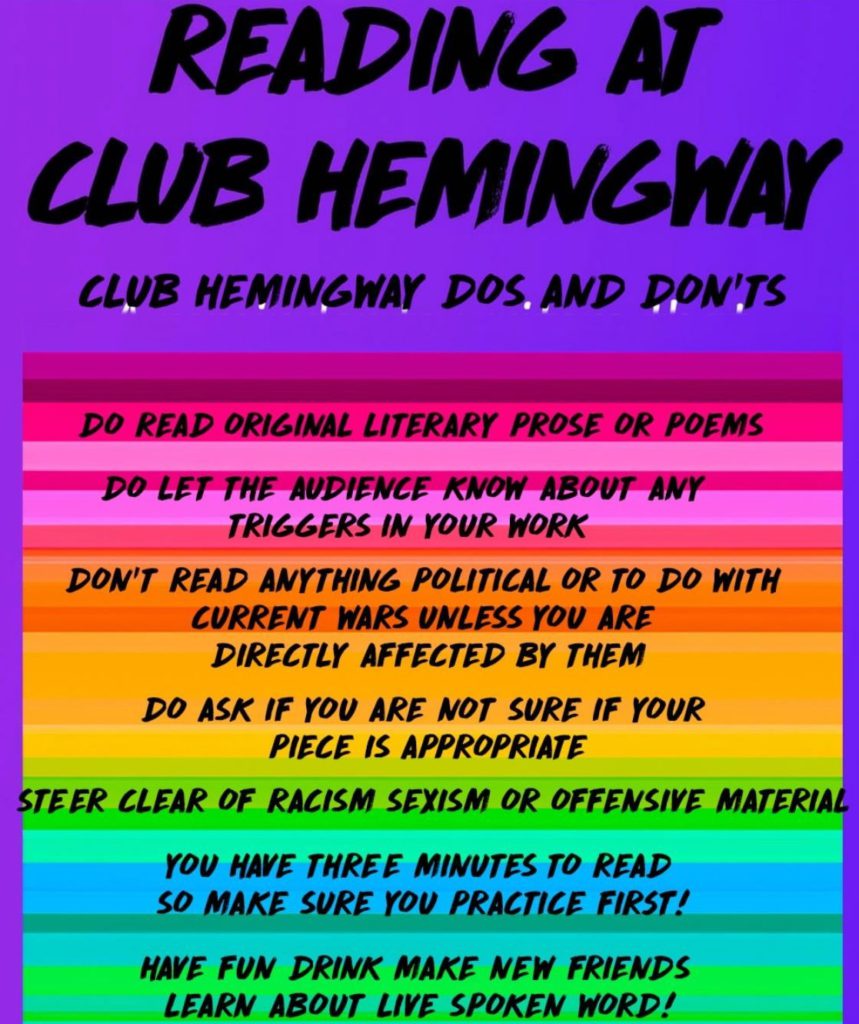

The day before the reading, the organizer posted rules for the participants and, with no clue how I would react (we had only met the prior day), he shared it with me:

Now, I’m a writer, both professional and amateur, although in no sense a literary person. I could not plot the arc of a good novel to save my life. I have no talent for fiction. Nonetheless, I love writing. Moreover, my social life is interwoven with many literary people, including my close friend, Susan Deer Cloud, a well published poet who is partly Native American.

I’m also not a person prone to let sleeping dogs lie. For years, I’ve watched with dismay the growing pressures on writers to limit their work. Accusations of “cultural appropriation” are rampant. It’s “wrong” to write from a perspective you haven’t lived or “authentically experienced”. There’s pressure not to write as a gender that you are not, to tell an ethnic story without being of that ethnicity, to write of trauma that you haven’t personally experienced. I’ve seen real world consequences repeatedly: accepted readings canceled due to opposition before the fact, anthology submissions rejected on political grounds, books unpublished on the basis of personal vendettas, or in Susan’s case, not being an Indian with official government recognition and benefits — a reservation Indian.

To me, it’s all bullshit. Freedom of expression is paramount. All the great ideas are likely to originate in some uncomfortable literary expression. Prior restraint is the death of revolutionary transformation. It’s the awkward, even offensive, writing and speaking that stretches human bounds and sows the ground for new views of life. I have always been a free speech absolutist. There’s no way to avoid the slippery slope of censorship once you first declare, “I will not allow you to say that!”

So, when I saw the above rules, I immediately took notice. My first thought was to not attend the event as a matter of principle. On further reflection, I felt the need to object to this imposition of prior restraint. I took a speaking turn prepared to rebut the wisdom of the above dicta, but failed. The organizer cut me off very quickly and, since it was not my event, I respected her authority and left the stage. I’m not an elegant public speaker. I could have done much better — but so could she. When ideas are suppressed, we are all the worse for it.