Prior post: http://blog.bucksvsbytes.com/2021/08/06/road-trip-21-06-21-the-mccarthy-road-former-railroad-track/

[NOTE: Some displayed images are automatically cropped. Click or tap any photo (above the caption) to see it in full screen.

We’re up early in our cabin ready to explore the Kennecott Mines National Historic Landmark, 5 miles along the old railroad right of way beyond the little village of McCarthy. Aspen Meadows B&B owner, Bonnie, brings down fresh muffins. These, along with juice, milk, coffee, and other supplies, put the second B in B&B.

Full of breakfast, we drive the 3 miles back to the McCarthy footbridge, again pay the daily parking fee, and hoof it across the Kennicott River. Yesterday was totally cloudy which precluded seeing any of the surrounding peaks. It’s another case of Alaska visitors having to settle for, “Trust me. There are some awesome mountains right there behind those clouds.” We’re in the Wrangell Mountains, which I know from many distant views in the old days are magnificent volcanoes rising to over 16,000 feet. One of them continues to show low level activity to this day. We couldn’t see anything above 6,000 feet yesterday and this morning isn’t any better.

In Alaska, I assume it’s going to rain or snow. You plan your outings anyway and any more hospitable weather is just a bonus. When I lived in Juneau, where it rains 220 days a year and is cloudy on most of the rest, we couldn’t wait for sunshine to play outdoors because we’d never do anything. We picnicked in the rain, played frisbee in the rain, and kayaked in the rain.

Since the mine site is 5 miles off, today we opt for the van waiting at the east end of the bridge and take the slow, rough, one lane ride to the Landmark entrance, trading stories with the driver all the way. To distinguish myself from the cheechako (anyone who hasn’t endured an Alaska winter) tourists, I invariably mention that I lived in Alaska for many years which generally triggers a narration of competing tales and reminiscences.

The Kennecott mining camp is linear, sandwiched between a steep mountain slope on the east and the Kennicott Glacier on the west. By the way, there’s no spelling typo in the preceding sentence. The glacier is spelled with an “i” but a clerical error in setting up the corporation resulted in the mine being spelled with an “e”. The mill building dominates the camp. The five copper mines are miles away in the high mountains, so ore was brought to the mill by an extensive network of aerial tramways.

Although the local Ahtna natives used copper for generations, its existence near the Kennicott Glacier became known to outsiders only in 1899. Geologists quickly determined that the site had the purest copper ore then known.

The mine ran from 1911 to 1938 and generated $200 million dollars worth of copper ore, more than enough to merit the extraordinary expense of such a remote operation and the 200 mile railroad built to service it. Everything was owned and funded by the Guggenheim and J P Morgan families (contemptuously known by their contemporary detractors as “Guggenmorgan”) and decisions were ruthlessly made on the basis of expected profit. It was a perfect example of the robber baron era. Kennecott’s namesake corporation later expanded with major operations in Utah and Chile that are still operating today.

When the ore ran out in 1938, the entire operation was shut down. Although some valuable and portable equipment was shipped out by train, along with personnel, the vast majority of the mining camp was left intact. The railroad was also abandoned in place.

Kennecott remained a ghost town for 38 years. During that period, the handful of area residents scavenged material and objects from the mill town. In 1976, the area was subdivided and lots offered for sale. Despite the difficult, remote access, a number of lots were developed by their owners.

When Wrangell-St Elias National Park was created in 1980, the Kennecott site became a large, private inholding in the middle of it. Very gradually, people started coming here to access the extensive wilderness and explore the abandoned camp, in which the private lots are interspersed. In 1998, the Park Service purchased most of the Kennecott site, excepting the lots that had been sold. It then began a collaborative but fraught process of preserving the mining heritage and encouraging visitors but maintaining the non-motorized wilderness character of a vast surrounding area, all while coexisting with Kennecott and McCarthy property owners. As you may imagine, this often does not go very smoothly.

Despite their remoteness, McCarthy and Kennecott attract tens of thousands of visitors each year. This is almost literally nothing compared to the hordes visiting Yellowstone and Yosemite but it’s still a large number for an area with such limited facilities. This year, though, because of the continuing closure of Canada to tourists, the visitation is way below normal. Most Alaska car rental agreements prohibit taking cars to McCarthy, so you pretty much need a private car to get here, or charter expensive air transportation. We’re one of very few out-of-state vehicles in Alaska this summer, and far as I can tell, we’re the only one here in McCarthy.

We start our walk through the town and are pleasantly surprised to find lots of interpretive signs that give meaning and context to what we’re seeing. Very substantial construction efforts are also underway to restore some of the deteriorated buildings so they can be safely entered. All the original buildings, except the hospital, were painted red by the mining company. Why? It was the cheapest paint color.

The old post office is now an exhibit hall, with 2 films about the park, a panel of mailboxes, and various artifacts and photographs. By the end, we’re getting a pretty good feel for what life was like for the miners — hard but reasonable. The mines and the mill operated year round. Frigid cold was just dealt with.

Our next stop is the company store, which is hardly changed from its operational days. Replica packages of items actually sold there re-create what it must have felt like to walk in. Unlike some company monopolies, Kennecott didn’t gouge its employees although prices had to be quite high just to operate at breakeven.

Ahead is the small Kennecott railroad station building , where passengers got on and off. Immediately beyond it is a wide wooden trestle, built for heavily loaded copper ore cars, across the rushing waters of National Creek with the town’s centerpiece looming over the far side. This is the 14-story mill structure — where the raw ore was concentrated and made ready for shipment to Outside refineries.

The mill is reputed to be the tallest wood building in the world, although it cheats a bit by not being free standing. Built into the steep hillside, it has ground support all the way from bottom to top. Although never demolished, the mill seriously deteriorated over the decades of abandonment. The roof was lost either to storms or salvage, and that allowed much further damage throughout the structure.

Private donors and the Park Service undertook various preservation efforts and now the mill is a major construction site as scads of engineers, workers, and equipment make progress on stabilizing the giant structure and eventually opening it to the public for interpretive purposes.

All we can do at the moment is admire its striking size and engineering from various exterior points and learn about the elaborate processes used to separate the copper from the various types of ore rock coming down the tramways in huge amounts. Starting with rock crushers at the very top and proceeding through a half dozen concentrating techniques, we’re amazed to learn that over the life of the mine, the mill extracted an astounding 97% of the copper content on site and sent it south by rail and ship. This was an incredibly efficient operation, designed to wring out every last bit of profit.

Since the rail line was often temporarily shut down for damage repair during winter and spring, much of the ore was stored in 140 pound sacks and loaded onto the next available train.

Leaving the main level, we follow rough roads and steep trails up the side of the mountain, circling around past the top of the mill where the tram-delivered ore was received and began being processed.

I should mention that wherever you are in town, a glance to the north or west encompasses stunning views of the glaciers and steep mountains. It’s easy to see why people went to great effort to build cabins and houses on the very remote Kennecott lots offered for sale.

The clouds have been steadily clearing all morning and as we walk the upper road, the sun is quite fierce and the distant views are constantly improving. The whole tenor of the valley changes for us as blue sky prevails over clouds.

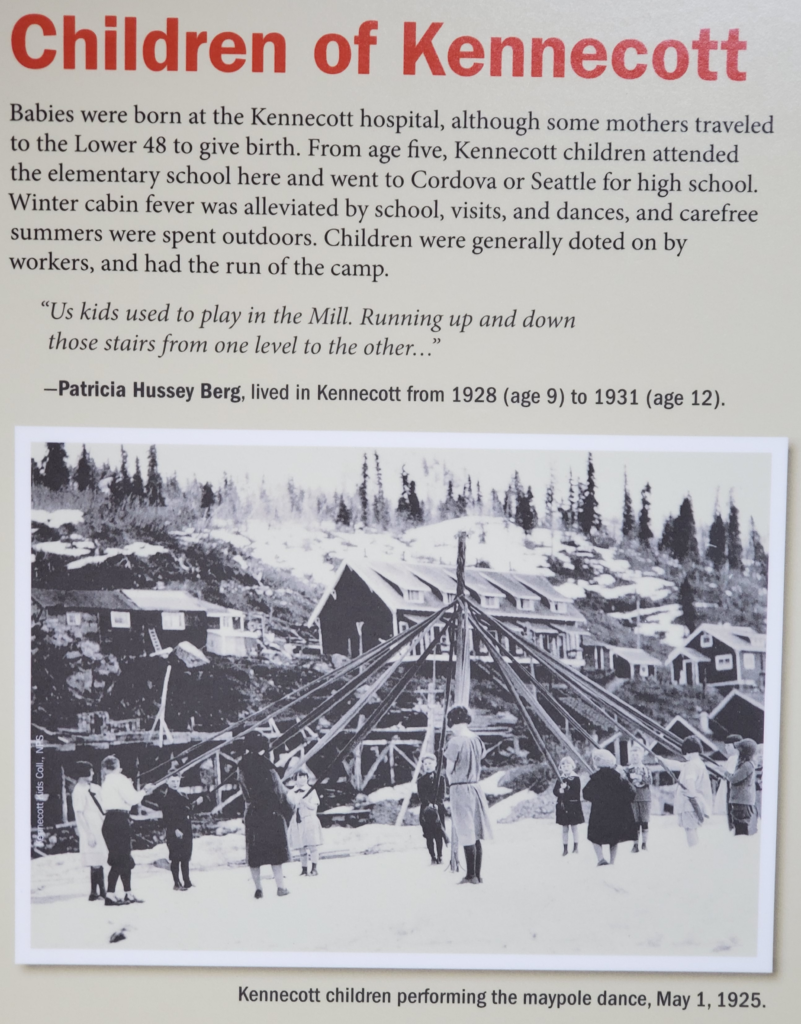

Coming back around and down off the mountain to the end of town, we find signs describing Kennecott family life.

Although most of the mine and mill workers were here alone with loved ones thousands of miles away, some of the management and clerical personnel lived here permanently with their families. The solo workers lived in large dormitories and ate in dining halls.

The white collar workers, whether or not their families were with them, lived in cottages or apartments.

By 3 PM, we’ve had our fill of gawking and reading and learning and walking, so we prepare to leave Kennecott. The clear weather is persisting and I suggest the possibility of chartering a small plane for a flight toward the high peaks of the Wrangell Mountains.

Inquiries at the office of the only flying service in town result in a determination that the flight pricing equates to an hourly rate of $600. This is absurdly expensive for a small plan, so we abandon the idea despite the good flying weather. We board the shuttle van back to the footbridge and return to our van on the other side. This is where [sarcasm alert] the fun begins.

As I begin to pull out of the parking lot. the van’s Tire Pressure Monitoring System (TPMS) warning is prominently lit. At least one tire is seriously below its required pressure, and TPMS often signals a fully flat tire. The area now serving as rough, rocky private parking undoubtedly has a rich history of prior uses and I immediately suspect some errant piece of historic metal has penetrated a tire. I guess I should be honored.

I put a gauge on the tires and find the right rear down to about 20 psi — at least it’s just a slow leak. Normally, I carry a 12 VDC tire inflator, but both of the ones I’ve brought have apparently reached their retirement age because they’ve stopped working so I don’t have the option of trying to make it back to civilization with repeated inflations. As I’ve said before, these are run-flat tires and can support the car — for a while — even when uninflated and, thus, there’s no place dedicated to storing a spare wheel. This could easily be the most remote place in remote Alaska to not have a spare (this later turns out not to be true).

I carefully exit the lot and head to a place a short distance away I noticed earlier that sports a “flats repaired” sign. The only structure there is an outhouse-sized shed. Looking inside, I see a note explaining that you leave flat tires on the left side along with cash payment. When repaired, they’ll be deposited on the right side for pickup. This arrangement is useless to us. With no spare, I can’t remove a tire and leave it for some unknown period, and I suspect the proprietor wouldn’t appreciate my demolishing the shed, small and flimsy as it is, in order to park the van so my bad tire is in the correct dropoff position.

Our only other option is to drive carefully back to our cabin and ask the owners for assistance. They’re, of course, happy to help and since McCarthy is a tiny place they know the person who operates the dropoff tire service. Reaching him at home during dinner, they arrange for me to meet him face to face at his shop at 8:30 AM to repair the tire. This is a wonderful outcome as it severely lessens the chance I’ll have to pump up the bad tire as high as possible and tear along at least 50 miles of rough road in hopes of making it to the next possible tire fixer.

With nothing left to do until tomorrow morning, we make dinner and spend our second and, we hope, final night in the comfortable cabin.