[NOTE: Some displayed images are automatically cropped. Click or tap any photo (above the caption) to see it in full screen.

I’ve been invited, on very short notice as usual, to stay with a Servas host named Abel in Madrid. As the biggest city in Spain, Madrid has real urban traffic and I arrive, after sitting in a jam caused by a freeway accident, at his house adjacent to the large San Isidro Park in a neighborhood just south of the Manzanares River which runs through the city. I find parking a 10 minute walk away in front of the large cemetery, load up my overnight gear, and walk down many steps to the house. Abel has warned me he lives on the 6th floor with no elevator. After he buzzes me in it’s a bit of a slog humping my way up all those stairs under load but I make it with some energy to spare. He lives in a 1-bedroom apartment with the major asset of a rooftop terrace, high above the street. He has hundreds of interesting books, most of them in Spanish, of course.

Abel is sort of a recluse these days, largely due the debilitating effects of long Covid, which limit his mobility and endurance. Photos he shows me, indicate a wild and crazy guy during his younger years, He adheres to a careful diet to combat his symptoms. On Sunday morning, Abel and I take a short bus ride to a major plaza. He shows me a few locales in the immediate vicinity and then leaves me on my own. One of the major attractions in Madrid is the Prado, the giant art museum. I know when Susan comes, the Prado will be an inevitable stop, so I’m not going to subject myself to it prematurely. Strange to say, Madrid does not evoke any favorable feelings in me. I guess I’m jaded by too many European old cities. I decide to just do a large walking loop through various neighborhoods and then back along the river, only 3.5 miles in total. Call me a barbarian, but that’s enough Madrid for me, at least for the moment. Back at Abel’s rooftop apartment, I spend the rest of the day with him and a small succession of female guests. One of them, Sophia, arrives with guitar in hand. She was born British but has adapted totally to life as a Spaniard. She plays and sings some of her original songs in Spanish. Interpreting for me in English, she points out various Spanish double entendres incorporated in her lyrics. The surface meaning is innocuous but the second one is something salacious or risque. It takes real command of the language to pull that off.

Sophia incidentally mentions that she has some facility in about 5 other languages, too. In light of the proficiency ceilings I encounter with foreign languages, she makes me look completely incompetent. I am so jealous of people like that.

Sophia arrived with a friend, Lourdes. In the course of the evening she reveals a lot of unhappiness with the way her life has turned out. I offer her what sympathy and encouragement I can but, of course, I have no power to make it better, She does teach me one vital fact, though. At least in Madrid, a hole in one’s sock with the skin showing through, is called a “tomato”. How did I get this far in life without knowing that?

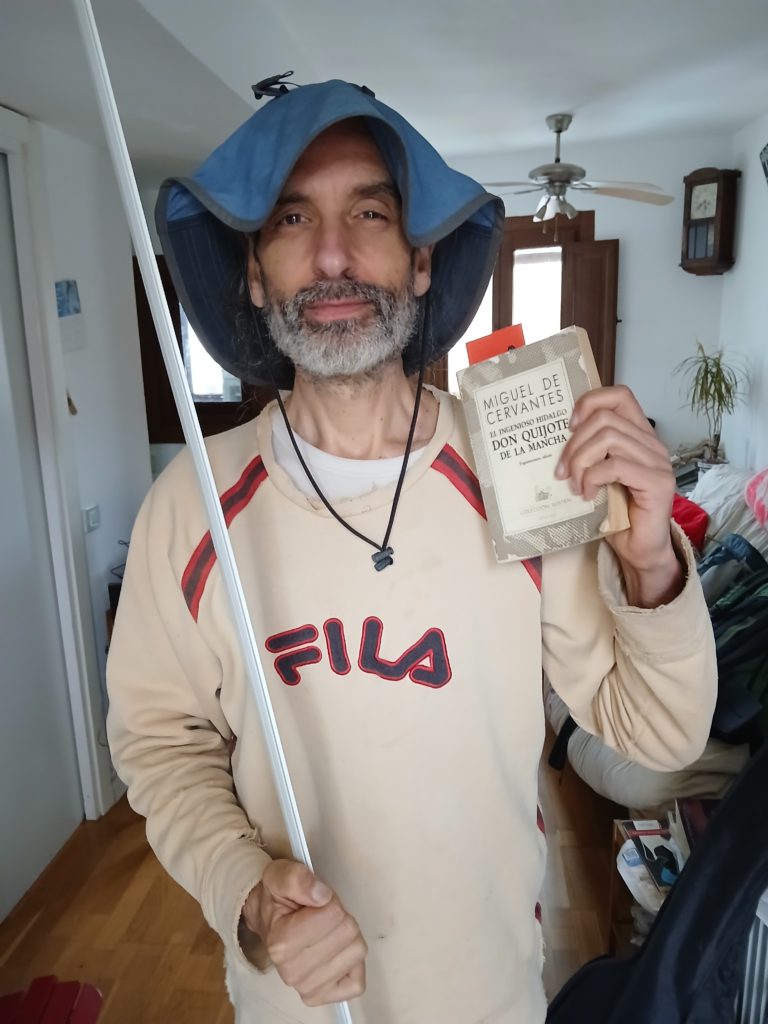

Late in the evening, the guests leave, Abel retreats to his bedroom, and I sack out on the couch for the night. Monday I spend time with him. At Susan’s request, he dresses up as Don Quixote for a photo.

After lunch I pack up and head uphill to the car. As I walk out the front door, a substantial rainfall is beginning. Just as I reach the car at the end of my 10 minute walk, the rain intensifies to a complete downpour. By the time I manage to unlock the Berlingo, shrug out of my backpack in the narrow space between cars, and get everything, including me, inside, I’m soaked. It’s nothing a half hour of heat can’t fix, though.

On my way northeast, I detour to an attraction I found in Atlas Obscura, a site dedicated to collecting a large collection of offbeat places. Many of them are uninteresting to me but a number of the ones I’ve checked out have been quite rewarding. Today, I stop in the tiny community of Civica, where an entire cliff is riddled with excavated cave rooms. Their purpose is obscure, and they’re said to have been sponsored by a local priest in 1950-1970. I arrive with the intent of exploring a little bit, but every access to the property is blocked off and prohibited. The only view I get, but it’s a good one, is from the road passing by.

I’ve booked a room at Hostal Las Nieves in a likely looking hiking area in Castile and León where potential hosts are quite sparse. “Nieves” means “snows” referencing the only ski area in this portion of Spain. I arrive about 6 pm, checking in with a young guy who seems like a new employee. He asks me how long I’m staying (this will turn out to be a significant question tomorrow) and I say at least one night, perhaps more if I like it. The room is very nice and I go down to the restaurant for some food. The owner is an Argentinian and, in true Argentinian style, his menu is laden with half pound Angus beef burgers. I order up one of the fanciest ones and thoroughly enjoy it. Best (and only) $20 burger I’ve ever had. That done, I go up to my room to spend the evening working and writing.

I pop up the next morning, having decided to stay, and go downstairs. The only visible staffer is a woman I haven’t seen before, presumably the owner’s wife. I ask her how much a second night will cost and she informs me that today is their rest day. I don’t quite understand. I already know the bar and restaurant will be closed today. As in the US, virtually every Spanish restaurant closes one or two days a week, but she seems to be saying I can’t stay another night. And she means just that: not only does the restaurant close today, the whole hotel does, too. Every Tuesday, all the guests have to vacate. I ask why the clerk from yesterday asked how long I wanted to stay if the place would be closed today, anyway, but she is unmoved. I’ve never heard of a hotel kicking everyone out for rest day, but that’s what’s happening here.

Now, I have just 2 hours to get out and find lodging for tonight. I do locate something not too far away and in the same price range, but I doubt it will compare to this deal. I make the reservation and start driving to the area I plan to hike today. Along the way, I see a small attraction sign for Monumento Natural de La Fuentona. “Fuentona” means fountain, so totally on impulse, I take a left and follow the sign. Driving a number of small roads, I end up at a deserted, dead end parking lot. The trail signs promise a waterfall and a spring, and that’s enough for me to start walking. The stream along which the trail runs is absolutely beautiful, water crystal clear so you can see the bottom perfectly.

Eventually, I come to a fork, waterfall to the right, spring to the left. I walk up the branch to the fall, It’s a very scenic spot, but there’s currently only a small seepage coming down the tall, vertical, moss covered slope. After watching the drip pattern in the small pool below for a while, I go back to the main trail.

It ends in a small pond that turns out be the outlet of a flooded cave system. If you’ve ever visited any of the well known Florida springs (e.g. Blue, Silver, or Weeki Wachee, the latter of the ubiquitous mermaid television commercials of the 1950s), you can imagine what I’m seeing: many gallons per second of perfectly clear water emerging from the earth under the pond. This is the source of the crystal stream I’ve been following. My random decision to follow a sign turns out to be a very rewarding excursion.

It’s now too late in the day to do my originally planned hike, so I drive a short distance north to my last minute lodging. Along the way, I see a tall tower off to the side so, Catskill fire tower fan that I am, I turn off onto a track that looks like it may lead there. It’s quite steep in places and on one pitch I need 4WD to make it up. At the top there is indeed a tower, but it’s deserted and the stairway is clearly off limits. Adjacent is a stone shelter that seems to have served as a traveler’s refuge at one time. Now it’s nonfunctional.

I arrive at Hostal La Tablada. Here, I’m assigned a 4th floor room, quite acceptable, but as often occurs I forget to test the wi-fi in the room before committing to it. The hotel advertises wi-fi “in all public areas”, which generally includes guest rooms, but at least all lobbies and lounges. After settling into the room, I try to connect — complete failure. I move down the hall to the guest lounge — same result. I talk to the owner about this and his attitude is “you can sit in the [ground floor] bar and use the internet”. The bar is loud and has no comfortable seating so that’s not a solution. My mention of his “all public areas claim” does not move him. I try relocating his wi-fi extenders, but they can’t pick up a 4th floor signal either. Eventually, I sit in the 3rd floor lounge, far from my room, and switch repeatedly between 3 sketchy wi-fi networks to get some access. Around midnight, the manager comes up and tries to blame the problem on the whole town’s unreliable internet service. This is bullshit, of course, because connecting to a wi-fi network has nothing to do with that network being connected to the outside world. I find his cavalier attitude annoying and that will be reflected in my review. All in all two frustrating hotel stays. In retrospect, I would have been better off in a dorm bed in a hostel. Note that in Spanish, a hostel offers dormitory bunk beds whereas a hostal is a small hotel with conventional rooms.

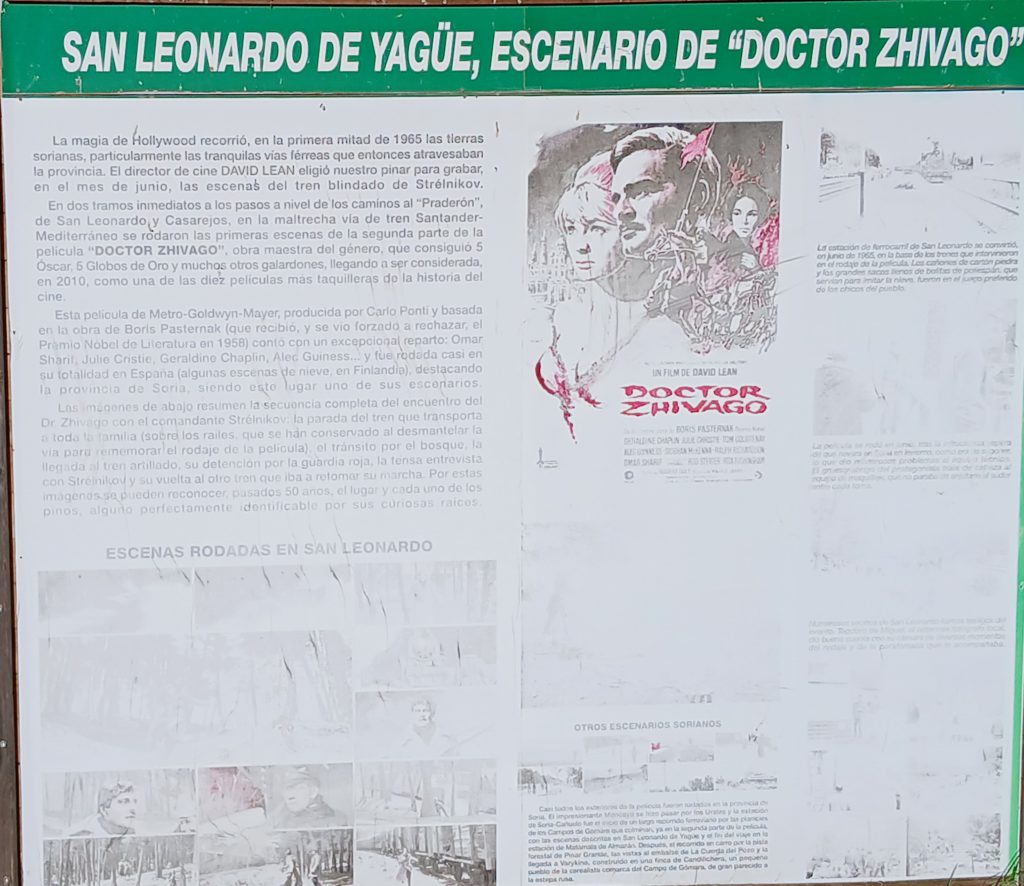

Wednesday morning, I proceed to the site of yesterday’s planned hike. A long and popular rail trail passes through the adjacent village of San Leonardo, along the ambitious but now defunct 500 mile rail line that connected Santander on Spain’s north Atlantic coast and Valencia on the Mediterranean. In the village, a station has been preserved whose claim to fame is that it was used to film a train scene (using artificial snow) in the movie Doctor Zhivago.

I’m heading for Cañon del Río Lobos (Wolves River Canyon). The approach road first offers a broad, east facing view of the canyon from high above.

I descend, get to the visitor center at opening time, walk in through the open door, and am politely told they, too, are closed for rest day. Checking the trail map, I decide on a loop through the canyon. The outbound trail goes up and over a high, rocky ridge. Shade is sparse at first but the air temperature is modest so climbing the long, steady slope is no hardship. Eventually the trail leads to another broad overlook, this one on the west side. The canyon is quite striking from above.

Walking further, the trail descends to the canyon floor through pine forest, emerging at a picnic area. Down here, spring is in full force and flowers are blooming.

I’m going to follow the riverside trail back to the car. I start that route but find that the Río Lobos, although it’s a narrow stream, is running quite high from recent rains. The trail crosses the river several times and rocks have been placed to allow dry crossings. Unfortunately, today, the rocks are all submerged and the fast running water does not give me confidence to try to cross them safely. It’s a situation where you have to commit to stepping on the next stone before knowing if it’s slippery and will dump you into the stream.

My only other choice is to walk over to the road and follow that back — not a desirable alternative. So, I decide wet crossings are the way to go. Ignoring the large, currently submerged rocks, I make my crossings easily along the stream bottom. In wilderness Alaska, almost all stream crossings are wet, and can be dangerous to the inexperienced or incautious. The situation here is safe but similar, with two major exceptions: I’m not carrying a full backpack that threatens to pull me off balance into the stream and the water, rather than being near-freezing, is not the least painful. All in all, a pretty trivial job. The only negative effects are walking along in soggy sneakers and wet pants legs after each crossing.

Nrear the end of the trail, I pass a small forest planted German-style, with the trees in a perfect grid, presumably for lumber quality and future ease of harvesting.

Eventually, I return to the car to leave the area.

In just a few miles, I pass an inconspicuous sign “Canal Romano”. Following that a short distance leads to something odd, the visible mouth of a 400 foot tunnel through rock that was part of a 25 mile canal reputedly built by the ancient Romans to serve their city, Uxama. If true, this work must date back to at least the 2nd century and their engineering skills were amazing for the time.

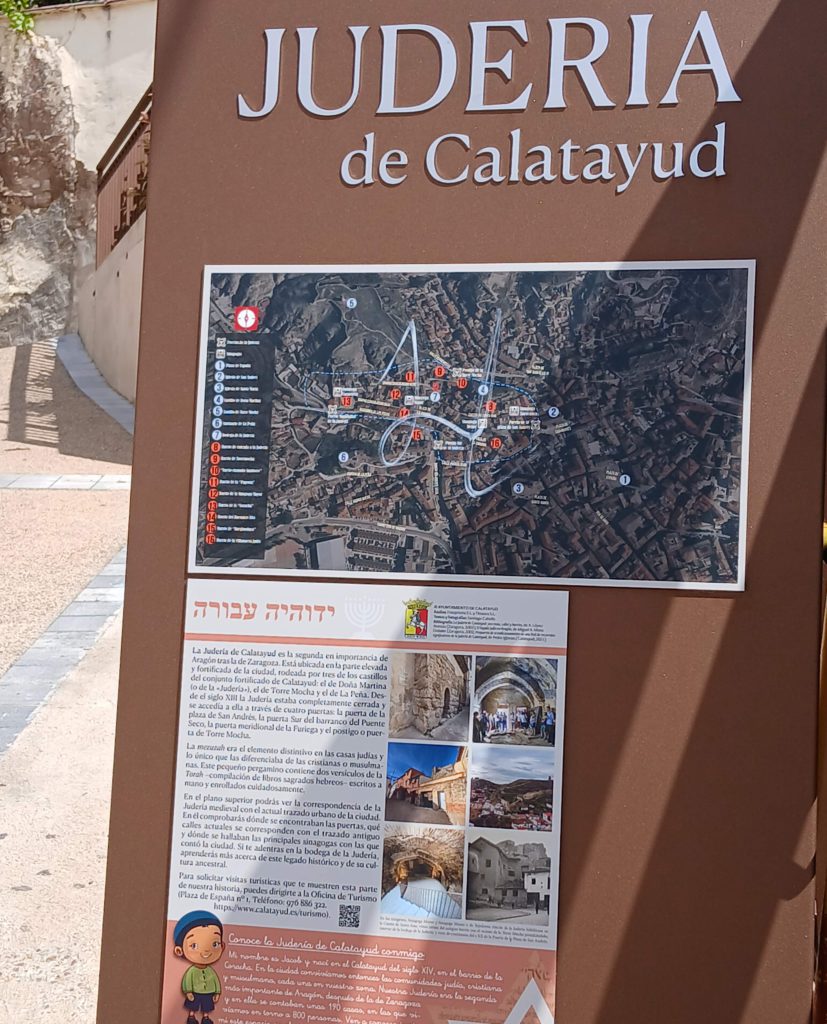

Now I drive a few hours east to my next hosts in another town I’ve never heard of until now, Calatayud. Servas members Maribel and Juanjo welcome me warmly. Maribel is 24 years younger than her husband and they appear very happily married. Their adult daughter is currently with them, studying hard for a make or break civil service test. Maribel’s mother, in her 80’s, lives in the flat just below and comes up every evening to watch her favorite quiz show with the family. Both Maribel and Juanjo speak some English, so when the discussion falters in Spanish, we can still find the right word.

We spend the evening talking, getting acquainted, and having dinner. I spend the night on the convertible sofa in the living room. After breakfast in the morning, Maribel, who just retired a few weeks ago from her government job in agricultural support, takes me to her now-former office and shows me around. I’m introduced to various employees, each of whom deal with farmers to help them comply with various EU regulations. She introduces me to Javier, a veritable fount of information, who suggests a couple of local destinations and, when he finds out I’m familiar with beavers from New York, Alaska, and Patagonia, gives me a half hour lecture on local beavers, who are both protected and inflicting environmental damage. Apparently there’s an ongoing process to mitigate their negative effects without killing them. The last thing we do is go up to the rooftop, only accessible to employees, for an impressive view of some of Calatayud’s historical buildings.

We then part company and I go for a walk through the town. Inevitably, I choose a prominent hilltop building, the Ermita of San Roque, as my goal, and end up walking up steep, twisting streets, in the sun, to the high point.

The view of the city and surrounding region is comprehensive and I sit in one of the few shady spots to enjoy it for a while. As it usually happens with my walks, it’s midday so there’s very little shade.

Right in front of the hermitage is a statue I can’t fathom.The inscription on the plaque says, “In memory of the deceased peñista.” After considerable research, I finally decide it’s a memorial to one or more dead local football fans. The fact that it’s sitting in front of a church confused me until I learned that Calatayud’s team is named San Roque, which is the name of the hill I’m atop.

From the hermitage, I can see Calatayud’s castle (there’s always a castle) on an adjacent hill. It looks impossibly far, high, and hot, so I set out for that. This involves a steep sunny descent to the valley between the hills and another long uphill slog to the castle. It’s a massive structure, built by the Moors. In fact, Calatayud is an Arabic name referring to the castle (qaliat) of Ayyub (an 8th century ruler who was the namesake, in English, of the biblical Job).

On the way up, I see a schoolyard far below me with students apparently at recess. In the bright midday sun, what are they doing? Sitting in a semicircle directly in the heat. I wonder if any Spaniard has heard of sunblock, a hat, or long sleeves.

At this point, I’ve had enough activity for the day. Fortunately, the walk down from the castle back to my hosts is shorter than the way up, and I detour only briefly to buy cold fluids. As I’m resting up before dinner, the bells of the Santo Sepulcro church that is their immediate neighbor start to ring loudly and intensely. The bell tower is perhaps 75 feet from the apartment, so the tolling is hard to ignore, especially since it goes on for about 5 minutes. After dinner and the nightly quiz show, I’m definitely ready to sleep.

Friday, I’m going to take up Javier’s suggestion and drive to Cañon del Río Mesa (Table River Canyon). I stop first, as advised, in the thermal spa town of Jaraba but it’s curiously quiet. The various baths, all commercialized, have locked gates and almost nothing else seems to be open either. Maybe it’s rest day.

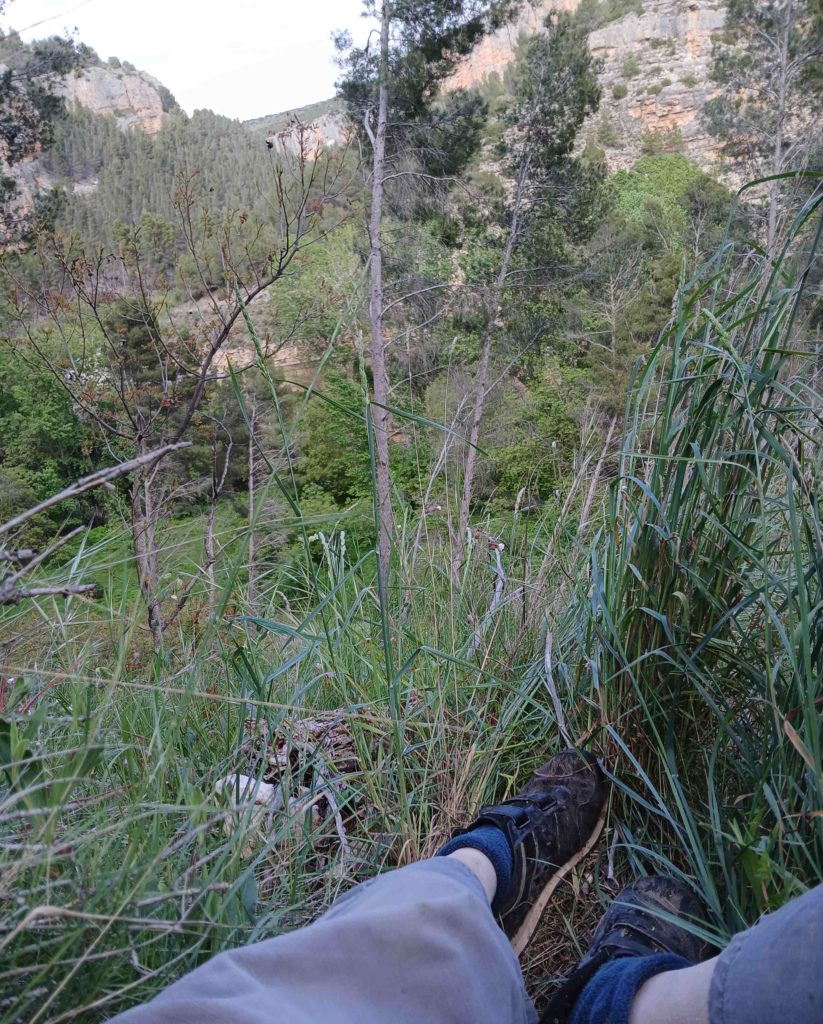

The canyon itself is neat. Steep walls, a winding river, and roadside caves make it visually interesting. However, the hike I plan to take is a problem. What my available resources indicate as the trailhead is a spot with no road shoulders and no possible route for a trail. It takes me about an hour of trial and error before I finally find the correct location in another direction, a trail sign for Mirador de los Buitres (Vulture Overlook). Parking the car nearby, I’m confident this is the right spot. The trail is a short one, from the canyon bottom to the rim, well under a mile. The trail starts out great, a clear signpost, a wooden foot bridge over the river, and another signpost. Piece of cake. I follow what looks like a well-used trail but, curiously, I see no more markers. None the less, the route seems clear.

Let me give you the end result right now to avoid suspense. The trail starts out left along the base of the canyon wall but after only a few hundred feet it turns sharply and goes right. It’s this switchback I miss, somehow. In my defense, the canyon wall is shear and clearly visible and I can see no way up in either direction. Thus I assume the trail will ascend the top of the large talus slope and eventually deposit me on the rim. Incorrect!

The seemingly clear trail starts to peter out. I’m torturously working my way up the difficult margin of cliff and talus, convinced this is the only feasible ascent. Above to my right is a 90 degree cliff, below to my left is a 45 degree slope.

Finally I get to a point where the going is so difficult that I have to leave the margin and cut side slope across the talus. This would be difficult enough if it were just rocks, but it’s covered with blowdowns. Some severe storm uprooted thousands of trees which are pointing down the slope at right angles to my path. Just to make it harder, the grass has grown tall, so many of the trees are hidden and it’s easy to stick my leg into an unseen void in the branches as I clamber over the trunks. Right in the middle of this mess, I get a phone call from Susan. I describe my current activity and now I know that if she sees my movement in this area stop for a long period, she’ll be calling out the troops. Succor for the sucker.

OK, I get through that portion and return to the top of the slope.

Remember, I’m visually convinced this is the only route to the canyon rim. Just to encourage me, by this point if I look straight up, I can see a structure that is almost certainly my destination.

I have to be on the right track. Another half hour of difficult progress and my remaining illusions are shattered. The canyon wall turns at a substantial angle — and the talus slope just ends. I can’t go up, I can’t go down, I can’t go forward.

Just before this, I had decided, once at the rim, I would hike the much longer “regular” trail back to the car, one I know is easier. No matter how long the walk, it’s preferable to retracing my last half mile. Bowing to the inevitable, though, now I brace myself to do just that. When there’s only one option, no matter how undesirable, you have to take it. It’s kind of like voting for the over-the-hill Joe Biden in 2020 because Trump was no alternative at all.

Going back is at least familiar. I know what to expect. At every step of the way, I can see, in the canyon bottom, the narrow Río Mesa and the adjacent road I drove in on. At several points, I look up and see vultures circling in front of the overlook. So as not to miss out on that experience, I get out my camera and shoot some photos of them from below. The view horizontally from the top would have been much more rewarding, but that ain’t gonna happen.

Once I’m again forced down into the talus slope and fallen trees, I decide that instead of going cross slope, I’ll head straight down. This is no easier because now I’m struggling along the length of the obscured trees instead of across them, but at least it’s shorter and gravity is with me. Whether that’s safer or more dangerous is an open question.

Being exceedingly careful not to get injured by catching my leg in a hole or losing my footing on a steep rock, I eventually make it down to the bottom, where the undergrowth is much thicker and harder to penetrate. Another ten minutes through a thorny thicket and I finally get to the river bank.

The stream is very narrow but too deep and fast for a wet crossing. The dense growth also makes it almost impossible to walk downstream to the footbridge. The road is so close and yet so far.

Scanning up and down, I see a tree whose branches more or less reach across the stream. I decide that’s my solution. Fighting my way to the tree, I get up a few feet and manage to inch my way across — the current is just below me — on two more or less parallel branches, one for my feet and the other for my hands.

Very fortunately, this technique works, although at the far end the branches are much too thin for comfort. Once across the stream, I fight through another 50 feet of brush to the road, Of course, being in a canyon, it’s built on a 20 foot vertical embankment. At this point, this is the easiest part of the whole day. I find an eroded portion of the otherwise sheer wall and manage to clamber up to the road. From there it’s a short walk to the car, and boy am I happy.

On the way back to Calatayud, at one of Spain’s ubiquitous traffic circles, the Policia Nacional are waving over drivers. I’m asked for my license — the New York one I present does not faze the polite cop at all — and asked to blow an alcohol test, which of course I pass. There is virtually no moving violation enforcement by police in Europe, no police cars with radar guns lurking for excuses to do a traffic stop as in the US, so I consider this a minor convenience.

I drive back to Maribel’s and tell my tale. They haul out detailed trail maps and we figure out, long after the fact, that I missed that very early switchback on the trail. In fact, Maribel was only aware of the long, easy trail to the mirador. The short ascent trail is new to her and I can see she’s looking at me as pretty crazy for choosing it. Not the hike I planned but a good adventure — in retrospect — because the residual Prussian in me knows you can’t have fun unless there’s some suffering involved. By that standard, I had several weeks worth of hilarity. It’s important to note that at no time was I sacrificing safety. Three hours to go less than a mile indicates my extreme caution.

In late afternoon, as dinner is being prepared, Maribel leads me to the window and points out the once a week dramatic night lighting of the adjacent church. As soon as the evening living room activities end, I’m fast asleep.

Saturday morning, I’m going to make the long drive to son, Eric’s, house near Girona. I plot a route that avoids major highways so I spend a good part of the day on scenic back roads. I have to say, I’m impressed with the Spanish commitment to road construction. At least 50 miles of my route is on lightly trafficked roads undergoing major widening, straightening, and repaving. Of course it may just be pork barrel spending, what I sarcastically call in the US the National Highway Contractors Full Employment Act.

Early evening, after a final stop for an oil change appointment at the local chain, Norauto, I arrive at my true home in Spain where I’ll spend time with Eric and take care of some other maintenance tasks before heading across France to Italy.