Wednesday, I say my goodbyes to Manuela and drive back south to another town north of Lisbon, not very far south of my previous stay in Marinha Grande.

I seem to have fully adapted to Spain and Portugal driving styles and traffic rules. It’s been weeks since I’ve even come close to killing a pedestrian. The three major issues here are crosswalks, traffic circles, and the white line.

Pedestrian crossings are the biggest thing. They’re everywhere, city and rural, marked by white stripes across the pavement but they come in two varieties. The uncontrolled ones always give pedestrians the right of way. If they step into the crosswalk it’s drivers’ 100% responsibility not to interfere with them. In Portugal, walkers check traffic briefly before crossing. In Spain, a significant fraction of crossers walk quickly and blindly across the street without a sideways glance. Since sight lines are often blocked by trees, vehicles, or buildings, these are the people that were most at risk in my first couple of weeks. As a driver, you have to scan ahead for crosswalks and then slow down even if they appear unoccupied. You never know when someone walking briskly, absorbed in their phone, will come darting out a side street and enter the crosswalk within a second or two of becoming visible. It seems like a Darwin test to me, yet these people seem to live into old age. In the US, we now also have pedestrian priority but sane walkers will stop at the curb and make eye contact with approaching drivers before stepping off. Portuguese pedestrians are typically a little more conscious of traffic than Spaniards. While crossing, they often give a wave of thanks for stopping.

The second kind of crosswalk — which in my opinion should definitely be painted a different color — has a conventional “Walk/Don’t Walk” signal governing when pedestrians can cross. Usually, these have a traffic light so when it’s green you can drive through with much less caution. Some of them don’t though which means you must approach slowly enough to yield until you’re so close you can see the red, pedestrian, Don’t Walk signal There’s also frequent jaywalking outside of crosswalks. I’m not sure whether, if I mow one of those people down, I get a free pass or not.

I’ve been invited by Servas host Sonia in Caldas da Rainha (Queen’s Hot Springs) but she’s warned me she’s very busy with work. On arrival, we introduce ourselves, She shows me the house layout and I meet teenage son, Gonçalo,. Sonia’s an assistant professor and within minutes she’s back on her computer working away. I’m so used to hosts being retired people, that it’s a shock to stay with someone young enough to still be working, but that’s the case here. Sonia is a single parent with a very demanding job and, except during brief meal interludes, over my stay we have little chance to get to know each other. She is either working at home or teaching and Gonçalo goes to the gym every day after school. Even so, she’s generously offered me hospitality, which I greatly appreciate.

The house is large and very comfortable, located in a suburb-like modern subdivision. In the morning, following suggestions from Sonia, I take off on a driving tour of the area. My first stop is nearby Óbidos, with a castle situated on the hill in the center of town.

[NOTE: Some displayed images are automatically cropped. Click or tap any photo (above the caption) to see it in full screen.

The castle is very large with an intact wall and a spacious interior courtyard. As I arrive, something strange is going on. Dozens of workers are assembling some big project. Most obvious is an ice skating rink and, adjacent, what looks like a ski jump except at the end of the ramp there’s no room to jump and land. I must be misinterpreting its purpose.

Just outside the castle gate is a replica (I assume it’s a replica) of a siege tower, a tall, heavy, timber platform on wheels as tall as the castle wall. It looks like they would load it up, outside of defensive range, with heavily armed soldiers, others would roll the platform against the exterior of the wall and mayhem would break loose. I would not like to be assigned to that duty.

Inside the castle walls, dozens of structures are being erected. Gradually, I figure out they’re building some sort of elaborate, temporary Christmas village.

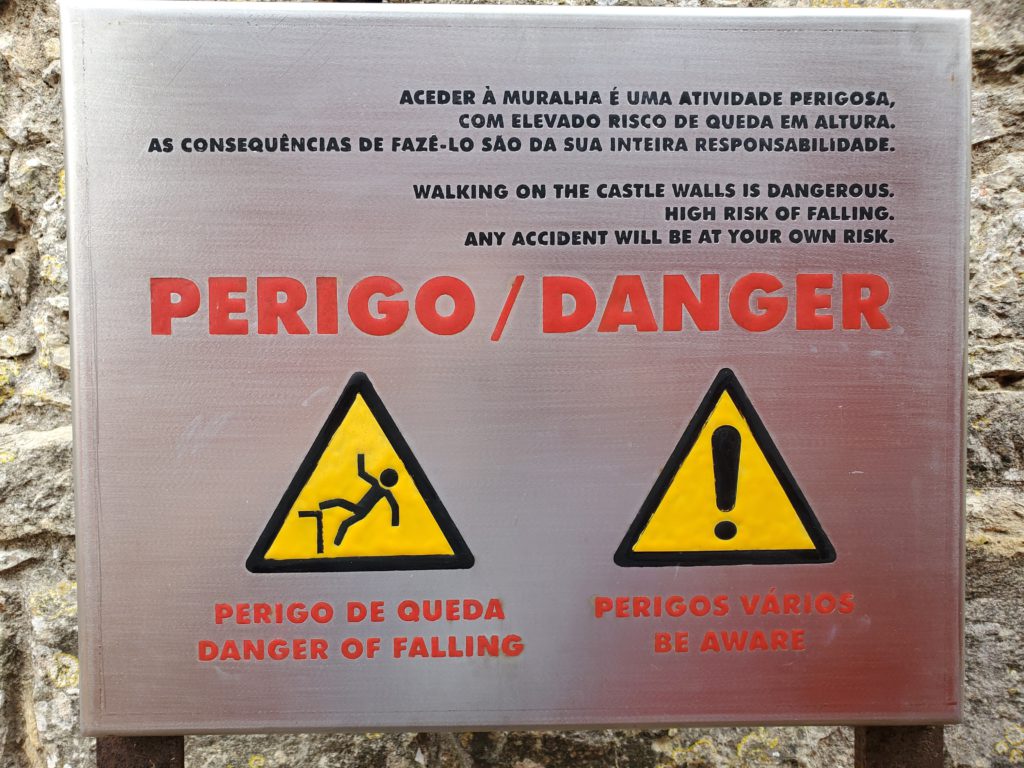

The public is free to walk through the busy construction site and I choose to go up along the somewhat terrifying stone steps that access the castle wall high above the courtyard. Although they’re just wide enough to walk more or less safely, one misstep to the unprotected left would be tragic.

In an abundance of caution, especially because I’m a bit unbalanced by the heavy camera bag over my shoulder, I ascend using both hands to grip recesses in the stone wall. It makes me look like a chicken, but I hate dying on vacation. It ruins the trip.

Down on the flats, in Óbidos proper is a fully intact, 2 mile long, stone aqueduct. Roman? No. It was built in 1570 by the queen of Austria as a gift to the town, Why the queen of Austria? Because she was the wife of the king of Portugal. Marriages among the nobility were often made for purely political reasons, as well as to avoid marrying your first cousin and producing hemophiliac and deformed children. I’m sure some of these involved genuine devotion but many of them must have been hell.

Next is the Óbidos Lagoon, a large body of water connected to the ocean by a channel. It’s an unusual environment and kind of nice, but in common with much European oceanfront, much of it is overrun with summer homes and businesses catering to vacationers. Any unprotected stretch is eventually swamped by development, including high rise condo and rental blocks.

On to Baleal, in the middle ages, an island sitting on the whale migratory route. The name itself refers to its important whaing past until, that is, the sandbar formed creating an isthmus from the mainland.

Digression:

Q: Use “isthmus” in a sentence.

A: after a moment’s thought, “Isthmus be my lucky day.” Our Gang, 1933

This prevented whaling ships from anchoring. so they moved on to more navigable waters. This sort of sandy isthmus has its own geographic term, tombolo. The rocky promontory is now a densely built tourist destination but one big storm could make it an island again.

The sandbar beach is a popular surfing locale, even in November it’s populated by dilapidated motor homes, surfer vans, and wet-suited young people speaking a variety of languages.

Beyond the crowded tourist portion of the town is the ruin of a never completed French fort, built during Napoleon’s brief occupation of Portugal in 1808, and archaeological digs of shell mounds left by neolithic inhabitants. The geology here is a textbook example of tilted sedimentary layers. The original horizontal deposits have been pushed up by tectonic forces. Remember, the whole Iberian peninsula is a tectonic plate that drifted toward and then crashed into modern-day France. The layers are now tilted at about 45 degrees — very dramatic.

Baleal is at the foot of the larger Peniche peninsula, occupied by the town of the same name. Also a rocky promontory, Peniche was an island until the 12th century when an isthmus formed. It’s geology includes a unique feature, the Ponta do Trovão. Here, there is an exposed rock face of ancient seabed containing marine fossils covering the 25 million years of the Lower Jurassic, an important evolutionary transition period. Interestingly, at that time, Iberia was located adjacent to today’s Newfoundland.

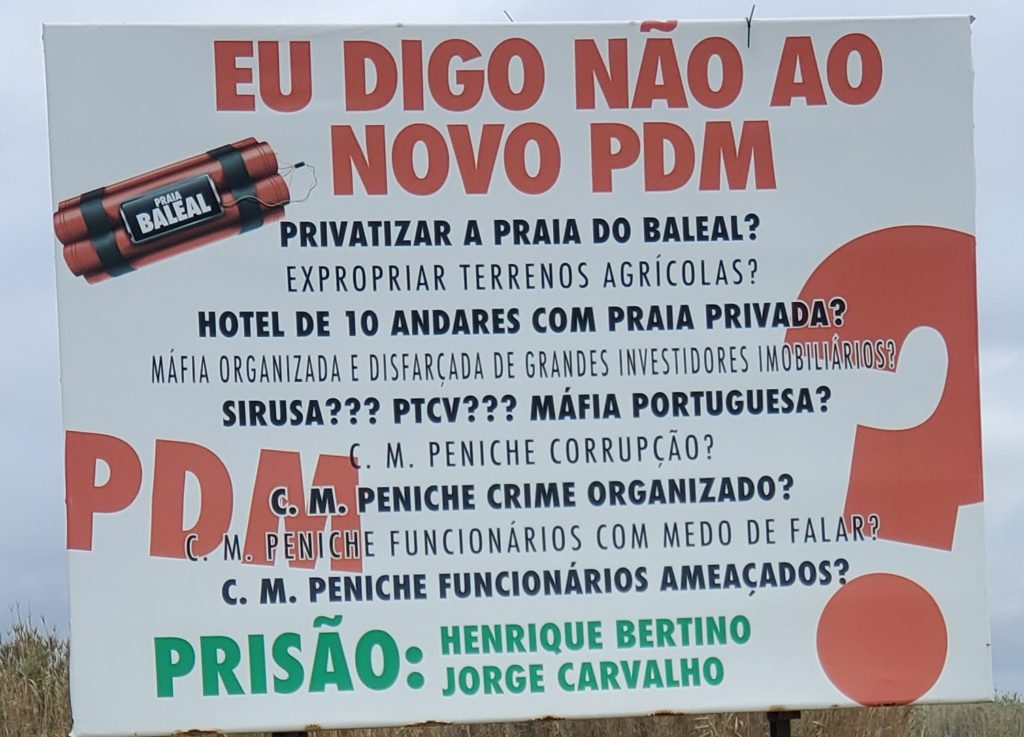

All along the shoreline are interesting formations and a lot of Atlantic Ocean history, and at least one political protest.

As I’m leaving the peninsula, I see a tree I know well but is very out of place. It’s an araucaria, or monkey puzzle tree in English. These very recognizable but endangered trees are native to the lower slopes of the Andes in central Chile and Argentina where I never ceased to marvel at their unusual shapes. Here is one in central Portugal, an interesting visual reminiscence.

From Peniche, I head back to Sonia’s. She is still working away when I arrive and a few hours later she makes a satisfying dinner for the three of us.

Early Friday morning, we breakfast on sourdough pancakes, Sonia and Gonçalo head out to their respective schools, and I gradually pack up and drive a little further south toward Lisbon. I have no host lined up and I need a little time with no social obligations to work on client issues and travel “overhead”, so I’ve booked a couple of nights at a hostel called, simply, Yard in Amora, a little south of Lisbon.

In a small town called Cheleiros along the way, I pass a small sign saying “Roman bridge” and wend my way around some narrow lanes and very tight corners to reach it. Even by European historical age standards, the survival of intact Roman structures intrigues me. This little bridge, exposed to the weather for 2,000 years, is still intact and usable though overshadowed by the modern highway bridge 200 feet downstream.

Along the way, I side trip to Sintra, a well known tourist town along the Atlantic coast. Within moments of arrival, I spot an antique trolley running along the side of a winding, hilly street. After getting some lunch, I go down a modest rabbit hole, spending a couple of hours along the route taking way too many photos and videos of the 1940 car as it wends its way from the beach back to town. The beach is fogged in, but the trolley is what holds my interest.

There’s only one car, so any unexpected failure could cause it to disappear forever.

After I satisfy that urge, I drive to the touristy part of Sintra, set around a deep ravine. Unfortunately, the topography traps fog so I can’t really see more than about 200 feet.

By the time I continue to the hostel, daylight is fading and I drive through Lisbon to Amora in the dark.