This is a reminiscence of a trip to Egypt in Ethiopia taken with my friend, Wendy Erb, in approximately December 1981. This text deals only with the Ethiopia portion of the trip. It’s not meant to be an absorbing narrative, but to preserve fading memories of a 40-year old adventure. Unfortunately, I have no surviving photographs so I’ve included a few internet-scavenged modern ones.

The year before, Wendy had visited me in Alaska, where I worked out an itinerary of wilderness and road excursions. Now, Wendy had managed to get travel agent credentials (she was actually an investment banker) and completely planned this trip. When we stayed in international hotel chains, we were paying only about half the normal rate. That may have applied to airfare, too.

Ethiopia has a long, storied, and often violent history. Its rugged terrain, fierce tribesmen, and periodic famines exempted it from the European colonization that overtook the rest of Africa. There is evidence of human and earlier hominid residence going back over 4 million years. We visited during the period of Communist dictatorship. In fact Ethiopia had just reopened to tourism when we arrived.

We fly from Cairo, Egypt to Addis Ababa, Ethiopia and transfer to the Sheraton hotel. After settling in our room, we return to the lobby and are approached by a young man speaking passable English who says he had earlier helped us with our bags and offers to take us on a tour of the city. Naively, we believe him and set out in a taxi he procures. I don’t remember how good the tour was, but we end up in front of a jewelry store. Looking at the prices we’re being quoted in Ethiopian currency, I suddenly realize they’re attempting to rip us off royally. Our tour guide is obviously in cahoots with the merchant and is scamming us — indeed, he probably just targeted us in the lobby and lied about carrying our bags. At that point, despite not knowing where we are in the city, we abruptly end the tour. To escape, we have to pay an extortionate taxi fare. Now we’re on foot, unaccompanied, unable to speak with anyone, and lost in a strange city. Fortunately, we can see the high rise portion of Addis Ababa and it’s a fairly easy walk downhill to the hotel. Chastened by our naïveté, we resolve to be much more skeptical of strangers.

Wendy, in her inimitable way, had made acquaintance with an Ethiopian in New York City. I think he worked at the United Nations. Somehow, she had arranged for us to meet with him in Addis Ababa. He was very urbane and educated and treats us to dinner at a restaurant. At that time, Ethiopian food was virtually unknown in the US and we have a delightful meal, during which he tells us a lot about Ethiopia. At the end of the dinner, as we part company in our hotel, he tells us, “Because you are foreigners, I had them cook the meat.” Realizing that the local cuisine often involves raw meat is quite a shock to us. Nowadays, many Americans are familiar with Ethiopian restaurants.

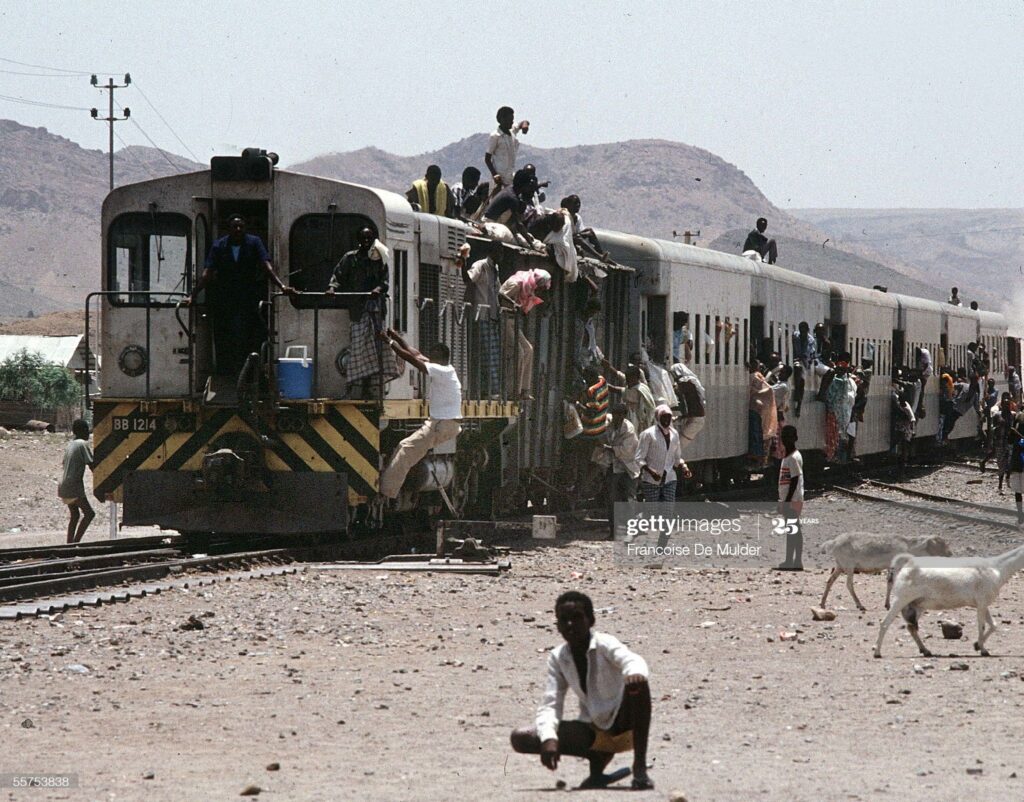

Our first tourist excursion is a road trip to the Dire Dawa region to see wildlife. I only have a few memories of that. One is being aware that this was one of the rebellious regions, but our guide assuring us it’s currently safe. Another is seeing the train between Ethiopia and Djibouti passing by teeming with passengers on the roofs of freight cars and hanging on to the passenger coaches. I don’t remember which way it was going.

Wendy has booked a loop tour around the country with three stops. Because of the rugged terrain and 3 ongoing civil wars, long distance road travel was not customary, so each leg is done on the government carrier, Ethiopian Airlines. We had entered the country on one of their routes, which was a modern jet and a typical international flight.

Internal flights turn out to be another matter. Because of the rebellions, security is very tight, and after going through multiple searches, all the passengers end up sitting in an unadorned, spare waiting room with no plane in sight. We’re eventually told our plane has been diverted to fly a football team to their match and we have to wait some hours for another one. More disconcerting, our plane is an old, unpressurized DC3 tail dragger and we have no idea if the safety standards for internal flights at all match those of the airline’s international operation.

Boarding the plane is not the typical flying experience, even for an Alaskan. Instead of conventional seats, there are two long benches facing each other, in the style of a military troop transport.

We each take a seat along the fuselage and buckle in. We’re the only foreigners on the flight and most of the others appear to be rural Ethiopians. For the young man to my right, this seems his first flying experience. Seeing others fastening their seat belts, he grabs a belt from his left and from his right but can’t figure out how to buckle them together. Why? Because he has two male ends, one of them mine. Puzzled, he starts to tie the two straps into a knot. I gently halt what he’s doing, hand him the correct end, and pantomime the proper buckling technique. Because a DC3 sits on the ground with the fuselage slanted downward from nose to tail, we’re all uncomfortably sitting canted about 15 degrees to the right on the canvas benches and the plane shows no sign of leaving the apron. Now the luggage is being loaded and, because the DC3 has no separate compartment, the handler is piling it all at the back of our cabin, opposite the door. Once loaded, he hooks a cargo net to the fuselage and squeezes all the bags and boxes behind it. It’s not a very secure way to protect us from the heavy objects in flight.

Finally, the door is closed, the two propeller engines are started and we taxi and take off. Since Addis Ababa is quite high at 7,600 ft and there are mountains between us and our destination, the unpressurized plane ascends to abut 10,000 feet. The passenger compartment definitely gets chilly but breathing is not noticeably impaired. Shortly after take off an old woman wearing a colorful , sari-like garment sitting across from us shows obvious signs of distress — she’s getting airsick. Strapped in on a full plane, there’s nothing she can do but progress to nausea. Just before she throws up, the man next to her pulls her shawl down over her head to give her at least a shred of dignity and privacy.

The engines are noisy and the aluminum skin vibrates loudly as well. Part way into the 200 mile flight, the cockpit door unlatches and I laughingly tell Wendy that meal service is about to begin. I mean this as a joke since the DC3 is small and consists of only the cockpit and passenger cabin. There’s no bathroom and no galley. The joke is on me as a uniformed stewardess emerges from the cockpit carrying a tray of drinks in paper cups. She works her way unsteadily down the aisle and we each grab what turns out to be something like Kool-Aid. She disappears back into the cockpit and shortly re-emerges, this time carrying a tray of simple sandwiches. Wendy and I are both amazed that there really is “meal” service. Fortunately, there is no turbulence en route. If there were, I’m sure the plane would turn into a vomit comet.

The late departure causes us to arrive way behind schedule at our first stop, Bahir Dar, a town is on the shore of Lake Tana, the 44th largest lake in the world. An attraction here is the papyrus boats used by the locals. We see some coming in laden with firewood from many miles away — a sign of the region’s extreme poverty. Although these boats are pitched to tourists as quaint and traditional, I quickly see how inadequate they are. Basically, the dry boat is put in the water and the occupant paddles like crazy to reach their destination before the papyrus becomes waterlogged and the craft sinks. It looks like a very risky mode of transportation.

I also remember feeling terrible that we’re being shuttled around in a Land Rover passing by people who are clearly economically destitute. Although we didn’t know it then, our visit fell between the 1977-78 so-called “Red Terror”, where 500,000 people died through government action. and the 1983-85 famine that killed one million Ethiopians.

We’re offered tej, a simple, homebrewed mead-like wine made from honey and a medicinal shrub. I don’t think it tasted very good to us.

Our main Bahir Dar excursion is to the Blue Nile Falls. We’re driven as far as possible and then walk across an ancient stone bridge (1626), where an ancient Ethiopian in some sort of uniform stands guard with an equally ancient rifle.

After tipping the guard to proceed, a further bit of walking brings us to a viewpoint across from the falls. They’re quite impressive, looking like a scaled down Brasil/Argentina Iguassu Falls. Since our visit, a new hydroelectric project has diverted much of the natural flow away from the falls.

The next morning we’re hustled back to the nearby airport for our flight to our next stop, Gondar. The airport terminal is a small, basically one-room, building facing a small apron connected to a grass airstrip. We’re checked in through the front door, then shooed about 15 feet through a one-table security station, out the back door to the building’s back porch. It’s crowded back there, so I descend the few steps to the ground to walk around a bit and am immediately confronted by an armed soldier who makes it non-verbally clear that I’m not allowed to leave the porch. I’m also not allowed back inside the building. Since there are about 27 passengers crowded onto the small porch, we get to know each other as time passes and no plane appears.

The bulk of the travelers are a West German tour group. My childhood German had recently been tuned up by having a girlfriend in Munich, so I get into quite a conversation with them. Over a period of 30 minutes or so, they teach me a number of East German jokes, a popular genre in the then-divided nation. The only one I remember is about East German Chancellor Walter Ulbricht making a radio speech to the nation. He says, translated, “I have good news and bad news. The good news is we’ve learned how to make butter out of shit. The bad news is that while we have the texture perfect, the taste isn’t right yet.” This referred to chronic shortages of staples and the frequent use of terrible substitutes in East Germany.

Eventually, we hear a plane approaching, but the sound soon fades again. Shortly, an airline employee comes out on the porch to tell us that the flight has been ordered to bypass us and another one will land shortly. After another 2 hours of waiting we all hear plane noise again. This time it’s for real because the cows grazing at one end of the runway are shooed to the side and the football game in progress in the middle is temporarily adjourned.

Another antique aircraft glides in, bounces onto the grass, and taxies up to the terminal. The loading process proceeds and eventually the planes engines rev up for departure — and rev and rev and rev. Finally, they’re shut down and we’re all shooed off the plane back to the porch. Some time later, a maintenance worker appears with a step ladder, climbs up to one of the engines, removes its cowling and peers inside. After 10 minutes of inspection, he climbs down, leaves, and eventually returns with a large container of liquid — engine oil, hydraulic fluid? We’re told nothing. He adds fluid to the engine, buttons everything up, climbs down, and disappears with his ladder. This little drama does not instill confidence in us. The passengers reboard the plane and we’re off to Gondar. By now we’ve lost two half days of tour activities due to flight delays but I’m appreciating that any successful flight is something to appreciate.

On arrival, we’re transferred to our hotel. After dinner, our guide herds us into an event room with promises of a folklore show. About two hours pass and still no performers arrive. The whole group is restless and annoyed. Wendy and I decide to walk around Gondar at night to get a feel for the town. Our guide urgently takes us aside and tries to convince us to stay. Seeing we’re determined,he takes us into his confidence. The mayor has told the guide to keep us inside for the night. Remember, we’re in a Communist dictatorship with civil wars in progress. As we speak privately, he decides to give us some background. Ethiopia has a Jewish population dating back to about 300 AD. The current regime is hostile to those Jews and has been, essentially, secretly ransoming them to Israel, which is flying them out, one planeload at a time. The mayor doesn’t want tourists wandering around and gathering information about this scheme.

After giving us this explanation, the guide tells us we’re free to leave the hotel for a walk but not to make contact with anyone, to which we readily agree. I don’t think the folklore show happened at all that night. The next day was spent touring Gondar. Writing this narrative, I’ve researched the city and read that it was an imperial capital for centuries and its attractions are very old castles and an Italian architecture dating from the brief occupation in the 1930s. However, 40 years after the fact, I can’t recall anything we did or saw there that next day. I know we flew on to our third destination, but I can’t remember anything about that, either.

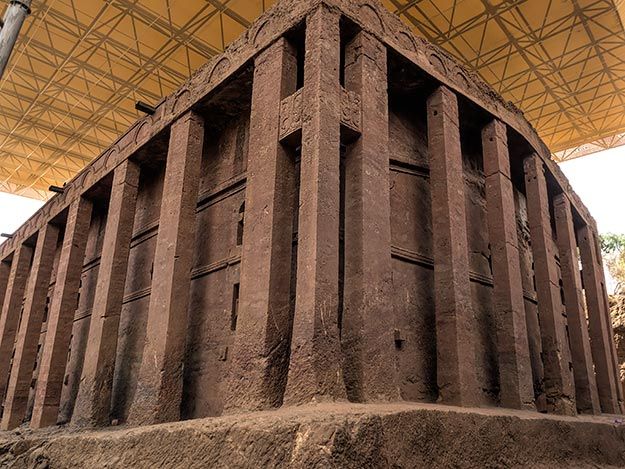

The Nile River region, including Ethiopia has had a strong Christian tradition, the Coptic Church, since the beginnings of the religion. In most of that area it was sidelined and persecuted as Islam came to dominate. The Copts are still the largest religion in Ethiopia, though, and since they have long been separated from other branches of Christianity, they have evolved different traditions and observances. In Lalibela, a number of ornate churches were, long ago, carved monolithically out of the sandstone terrain. It’s these that we came to see. Of course, I have almost no interest in religious sites but this is one of the marquee attractions in the country, so Wendy put it on our schedule.

On arrival in Lalibela, we’re lodged in a motel- or bungalow-like hotel with accommodations surrounded by gardens and paths. In the evening, I go walking and exploring the grounds and say hello to a young couple sitting in the gardens. They turned out to be East Germans. Though neither of them spoke English, I spoke German so we began a conversation.

They are both doctors, sent to Ethiopia as part of an aid project from one Communist regime to another. We start to get acquainted and they tell me how lucky they are to be chosen for an overseas job. Within minutes, though, the wife excuses herself and leaves. She is concerned that associating with an American could jeopardize their posting. The husband, Gerd, and I continue speaking for quite a while in the gathering dark about East Germany, his experience in Ethiopia, and my German background and experiences. I resist the strong temptation to recite my recently acquired East German jokes to him. By some quirk of memory, I can still remember his full name, 40 years later, despite the brevity and casualness of our encounter.

The next day is a blur of walkthroughs of what, in retrospect, seem like a dozen massive, rock hewn Coptic churches. My main memory is that they were all red, being carved out of the sandstone bedrock. I see a lot of Christian symbols that seem different from the ones that permeate the west. My impression is clearly of a religion that has lost contact with its foundings and has evolved into a “dialect” of Christianity.

Our final Ethiopian experience is another DC3 flight back to Addis Ababa, where I have a complaint to lodge. The monopoly tourist agency is the only place to buy in-country tours, most of which depend on flights by the monopoly air carrier. Due to the capricious operation of Ethiopian Airlines, where it seems government functionaries often disrupt scheduled flights and arbitrarily divert them for other purposes, we and other tourists missed out on a substantial fraction of our tour activities, spending our time instead sitting in airport waiting rooms and planes on the ground. Although both airline and agency are part of the government, the agency has taken no responsibility for our abbreviated tour schedules, saying they have no responsibility for airline delays.

On our last day, I hoof my way over to the agency headquarters and discuss the problem with the manager. I point out how bad it is for the agency and airline to get a reputation for failing to deliver on their commitments. I’m sure my complaints will fall on deaf ears, but the manager relents and gives me a modest rebate on our tour fees. Shortly after, we head for the airport and catch our jet back to Cairo.