Prior post: http://blog.bucksvsbytes.com/2019/10/27/south-america-by-subaru-10-20-19-goodbye-santiago-chile/

[NOTE: Some displayed images are automatically cropped. Click or tap any photo (above the caption) to see it in full screen.

Everyone is up early at Hostal Berta. The nine Brazilian women bikers are leaving this morning for Argentina, as are we, so there’s quite a ballet around Berta’s two bathrooms. The mountain spring morning is clear, cool, and crisp. As we’re all eating breakfast, pictures are taken and one of the women, Sula, invites us to visit her in Florianópolis.

Brasileñas

Berta looks a little chilly

Brasileñas

Brasileñas

Brasileñas

Once they mount up and roar off. we throw our bags in the car, say our heartfelt farewells, and continue eastward.

The highway twists its way along the Aconcagua River, gradually approaching the steep ascent to the Andean pass that marks the international border. This is the 4th time I’ve driven over Paso de los Libertadores, and I’m awestruck every time. The wide shouldered, two lane, well paved road winds its way up the steep mountainside in about 30 switchbacks. This section is named Los Caracoles – The Snails – for reasons that are quite clear when you’re looking down the mountainside. A parade of semi-trailers and double-decker buses inching their way up or down share the route with smaller vehicles. Many people write how dangerous the road is, but it’s beautifully engineered and competently maintained. Visually, though, it has the potential to scare the hell out of drivers and passengers alike. The road ascends to over 10,000 feet and chains (which we always carry) are required during frequent snowfalls. In extreme conditions it can be closed for days.

Not to waste a long, steep slope, the sinuous road has a ski area overlaid on it. The chairlift sails above the road numerous times but, fortunately, the ski trail doesn’t have any grade crossings of the busy highway.

All the way up, the old railroad clings to sheer walls, the railbed blasted into the cliff or bypassing particularly treacherous sections through short tunnels. At the bottom, the tracks are far from the highway and near the top rails and road finally converge. The original 1910 engineering and construction were a marvel. It must have been some ride, although it’s said trains would be stranded for hours or days by snowfalls. Even under optimal conditions, train speeds up and down the steep grades were minimal. Specially designed locomotives used sections of cog railway to ascend and descend the steeper sections on both sides with the aid of rack and pinion traction.

I would have loved to take that ride but, these days the route, though clearly visible all the way up, is greatly decayed, rock slides having blocked or wiped away many sections of the abandoned track. There are persistent but unrealized plans to reconstruct the route but they involve building a super long, low altitude tunnel along the lines of Swiss rail solutions. This would be much more reliable but far less dramatic and I doubt it will ever happen. Modern highways, trucks, and airliners have made railroads largely obsolete except for carrying bulk materials like ore, coal, and industrial chemicals.

The original auto route went 2,000 feet higher to the true pass, where, in 1904, as is mandatory in all Catholic countries, someone built a 4-ton statue of Christ the Redeemer. Google Maps still claims you can drive the old road and bypass the current tunnel, but on every trip I scrutinize the turnoff on the Chilean side and decide it looks too abandoned and sketchy to chance it. Perhaps in midsummer it’s snow free and navigable, but the only time I crossed the pass at that time of year, I didn’t know about that theoretical option. Every other time, the route definitely ascends above snow line, with no signage or evidence of maintenance. From the Argentine side the road looks better, but so far I’ve had no desire to drive a long dead end to see a religious monument.

Instead, we drive, as usual, through the well engineered but boring (get the pun?) 2 mile Cristo Redentor tunnel, squeezed among the buses and trucks that fill the oval cross section to within inches of the walls. Emerging on the Argentina side, we enter a broad valley that gently descends without the need for switchbacks. Here the old rail tracks meander along their own route, covered with long runs of snow shed built to ease winter maintenance. Many of the sheds are collapsed in yet another poignant reminder of technological obsolescence.

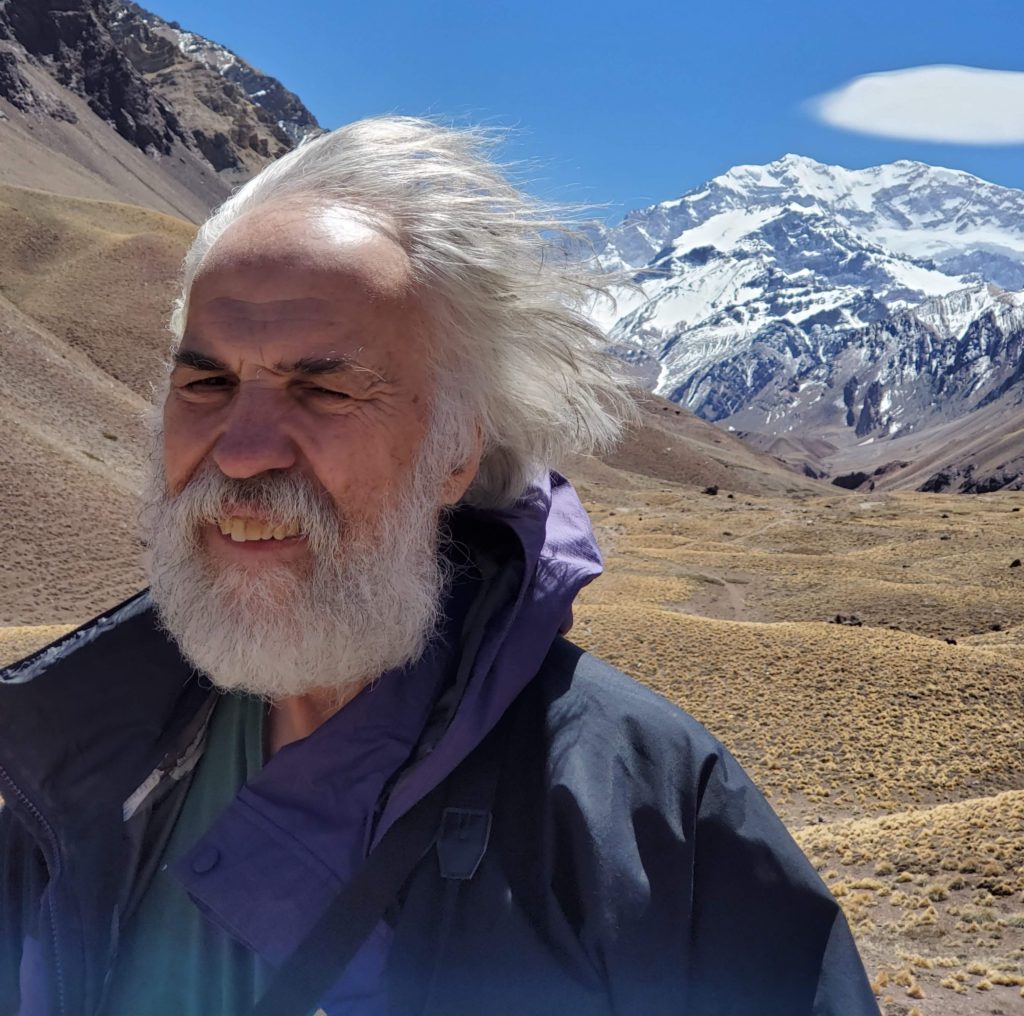

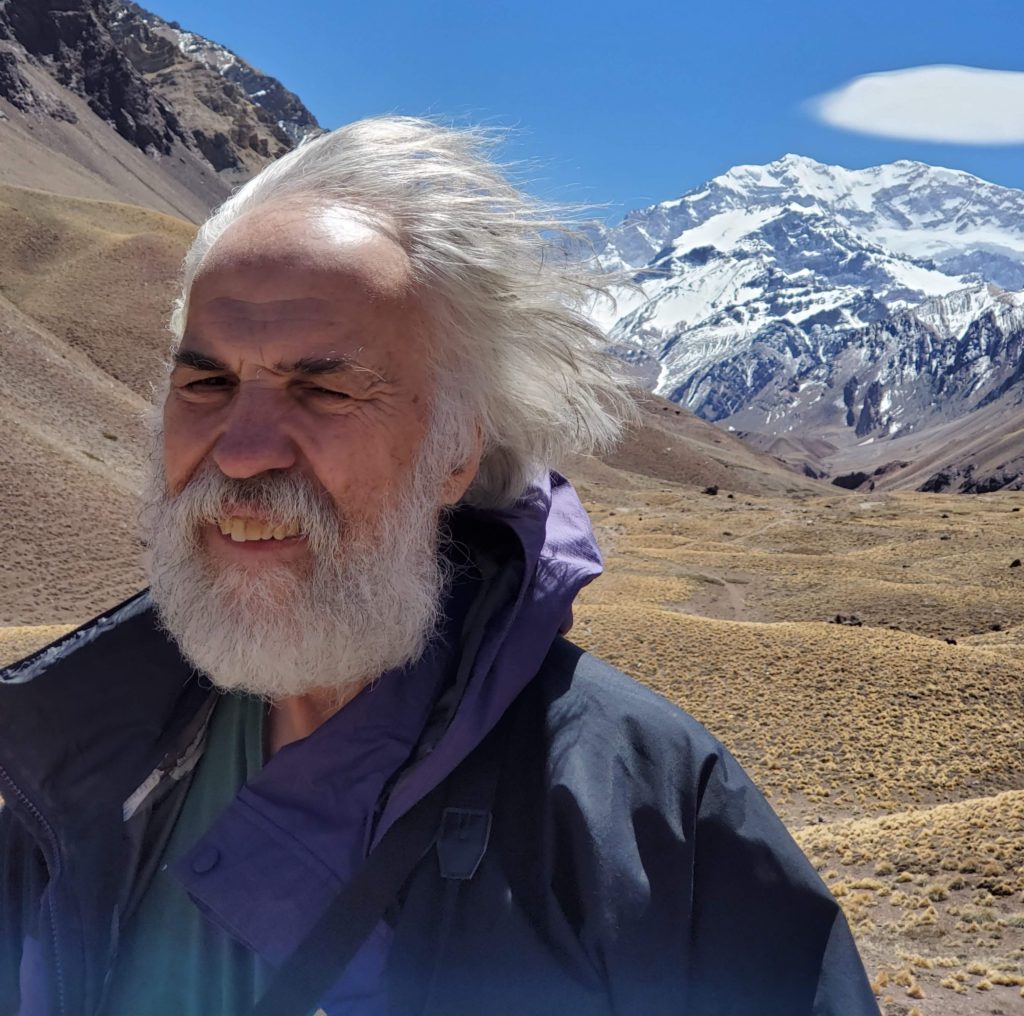

Entering Argentina, the integrated Chile-Argentina border post is over ten miles past the actual border. A mile before that is Aconcagua Provincial Park. The highlight here is Mt Aconcagua, the highest point in the western hemisphere. There are no good views from the highway and on the three prior trips, weather or park hours stymied our desire to see this enormous mountain. This time, finally, the sky is clear blue and the park is open. We pay the entry fee, drive a short way up the side valley and walk the loop trail that offers unobstructed views of the peak, which lies about 7 miles distant. As a former Alaskan who often boasted about living near Denali, at 20,320 feet, the highest point in North America, it’s humbling to realize that Aconcagua is 2500 feet higher. Not only that, but 45 other Andean peaks overtop Denali as well. There’s no Denali boasting in South America. The unobstructed view of Aconcagua is awesome, and we’re very gratified to finally see it.

Here are some more photos taken during our walk:

Aconcagua trailhead

Enormous, prominent stratified, tilted ridge (sedimentary or volcanic?)

Closeup of glaciers high on Aconcagua

Susan with Mt Aconcagua

Birds of Aconcagua:

Unidentified duck

Andean goose

Unidentified bird

Unidentified bird

Unidentified bird

High mountains often generate their own clouds that sit over the peak and curve along its profile. These are called lenticular clouds for their characteristic shape. In my experience such clouds are quite stable and stay over the peak for hours. Aconcagua, though, had a fascinating sequence of constantly changing lenticular clouds, an indication of ferocious winds at the summit.

Aconcagua’s ever changing lenticular cloud

Aconcagua’s ever changing lenticular cloud

Aconcagua’s ever changing lenticular cloud

Aconcagua’s ever changing lenticular cloud

Aconcagua’s ever changing lenticular cloud

Aconcagua’s ever changing lenticular cloud

Aconcagua’s ever changing lenticular cloud

Aconcagua’s ever changing lenticular cloud

Susan with Mt Aconcagua behind

Aconcagua’s ever changing lenticular cloud

Aconcagua’s ever changing lenticular cloud

Aconcagua’s ever changing lenticular cloud

Aconcagua’s ever changing lenticular cloud

Returning to the car and the highway, we next face border formalities. Generally our border crossings have been routine but every official in the gauntlet has arbitrary power and anything can go terribly wrong. Witness our problem last November, during our prior road trip, when Chilean Customs absolutely, unpersuadably wouldn’t allow us to take the Subaru out of northern Chile to Bolivia because we were not Chile residents, unexpectedly forcing us into a 2,600 mile detour (!!!) back south to where we are now and north to Bolivia via Argentina.

The border facility here is integrated, with Chilean immigration and customs sitting side by side with their Argentine counterparts. Given our prior disaster, we’re understandably stressed. As expected, though, everything goes smoothly, the final step being a perfunctory car search by a friendly Argentine customs officer before being released into the country.

The highway down from the pass traverses an impressively austere route, paralleling both the river and the forlorn abandoned railroad. After a couple of hours we reach the junction town of Uspallata, where I’m pleasantly surprised to find that gasoline in inflation-ravaged Argentina is substantially cheaper than in Chile, though still expensive by U.S. standards. The leftover currency I had from our last visit has lost about half its value in the intervening 11 months. Foreign tourists don’t have problems because the exchange rate compensates for inflation. We use mostly credit cards and only pull small amounts of cash from ATMs because (a) it starts shrinking the moment you put it in your wallet and (b) the ATM fees for foreigners are a staggering 12%, although ours are reimbursed by Schwab. The Argentines, however, suffer financially because their earnings don’t keep up with inflation driven price increases. Except for the rich, things are really rough here although there’s no sign yet of Chile-style unrest.

We’re heading for Mendoza, the gateway city a couple of hours southeast, but instead of again taking the main highway, we decide to take a route across the mountains through the Reserva Natural Villavicencio that, on the map, has a gratifying number of twists and turns. We start out on the well maintained gravel road, climbing gradually. Fifteen miles along, we pass a mine entrance and immediately past that the road condition deteriorates. It’s still very driveable but much bumpier with many rocks on the road.

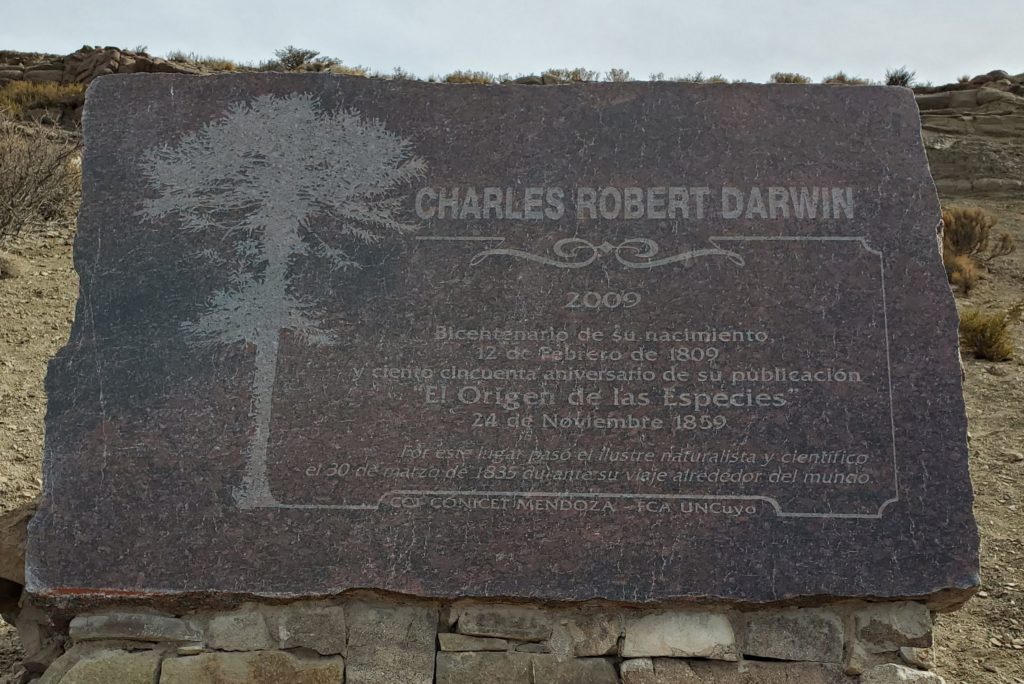

Half a mile later, we see what looks like a modern gravestone a bit above the road to the right. The name on it says Charles Robert Darwin. This of course piques our curiosity so Susan trudges up the short, steep hill to read the details. It turns out the stone memorializes that Darwin traveled this route on his way back from Mendoza to the H.M.S. Beagle, anchored at Valparaiso. That 500 mile round trip on muleback must have been some rugged journey in 1835. I’m almost ashamed that we’re breezing along in our 4WD Subaru Forester — almost.

Some minutes later, we see a dog trotting down the deserted road toward us. As we get closer we realize it’s not a dog but an Andean fox. We stop and the fox stops, not showing any great fear of us, and we commune with it for several minutes and take some closeup photos. This is the first time I’m putting our new camera, a Panasonic DC-FZ80K, to actual use and I’m very pleased with the results. Although it sells for a modest price and is not nearly as bulky as an expensive SLR, its 60X optical zoom, very good optics, and many convenience features quickly convince me I made a good choice.

The road continues ascending gently to about 3000 feet above Uspallata and then begins a twisting, dizzying descent. Instead of the 4300 foot drop on the main highway to Mendoza, we’re now carefully navigating a rapid 7300 foot elevation change. The road is rough and I’m constantly picking my way around pretty large, sharp rocks. We unexpectedly encounter guanacos. Generally, they’re very skittish but this group let’s us get quite close.

We stop frequently to enjoy the views and take a break from the necessarily cautious driving.

At one point, I misjudge the my track by a couple of inches and run the front right tire over a sharp edged, softball size rock. This is the kind of mishap that can ruin a tire, wheel, shock absorber, or spring, but we seem to have escaped any damage. Continuing down the winding slope, we finally encounter paved road at a hot springs resort.Termas Villavicencio. I had harbored some hope that it might have affordable lodging but, in addition to looking very expensive, it’s closed for the season. As we’re looking beyond the locked gate, a woman picnicking nearby walks over to us and says we have a flat tire. Visual inspection confirms that the right rear tire has lost most, but not all, of its air. I don’t think we’ve done any damage by running on it but it definitely needs immediate attention. I dig out the tire inflator to see if I can refill it and slowly, slowly, it comes up to an acceptable pressure.

Now that we have paved road, I’m hoping we can make it to Mendoza without mounting the spare. I stop to check the tire every 10 km or so and it’s evidently just a slow leak that I can drive on.

We race into Mendoza before the tire deflates again. It’s now evening so repair will have to wait until morning. Using my trusty booking.com technique, we locate a very nice hostal, Casa Huésped, that offers a clean, comfortable room, private bathroom,, breakfast, and courtyard parking for only US$17. The proprietress is a little brusque but accommodates us with a room away from the busy street. Hungry but lazy, we head across the street to a shopping center, and have plates of ravioli and a giant Quilmes Stout, Susan’s favorite Argentina beer – mine too, if a person who doesn’t particularly like beer can be said to have a favorite. The meal is tasty and cheap and, once sated, we walk carefully back to the hotel in the dark and are soon asleep.

Next post: http://blog.bucksvsbytes.com/2019/11/01/south-america-by-subaru-19-10-22-rest-day/